What’s in the black box? As we go forward we will need a model and machine readable bill of materials.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that we’re going to need an AI bill of Materials (AIBOM). Just as with a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM), there are a set of potentially important questions when we take advantage of an AI model, which we’re just not set up to meaningfully answer at the moment. The You Only Live Once (YOLO) approach that OpenAI took when launching ChatGPT is not going to provide end users with the confidence they need to adopt AI models in strategic initiatives. Sure we’ll see shadow AI adoption (like shadow IT adoption, but for AI tools), by marketing departments and sales and so on. The lines of business won’t allow governance to get in the way of productivity. But as ever bottom up needs to meet top down, which is where governance comes in. From an enterprise perspective we will need to get a much better understanding of the models we’re using, and what went into them. Which is to say, a bill of materials. Trust and safety are not the enemy. We need to better understand the AI supply chain.

The AIBOM will need to consider and clarify transparency, reproducibility, accountability and Ethical AI considerations. After introducing the idea of an AIBOM to Jase Bell he began to work on a schema, which you can find on GitHub here. It’s a useful starting point for discussion so please check it out.

Transparency: Providing clarity on the tools, hardware, data sources, and methodologies used in the development of AI systems.

Reproducibility: Offering enough information for researchers and developers to reproduce the models and results.

Accountability: Ensuring creators and users of AI systems are aware of their origins, components, and performance metrics.

Ethical and Responsible AI: Encouraging the documentation of training data sources, including any synthetic data used, to ensure there’s knowledge about potential biases, limitations, or ethical considerations.

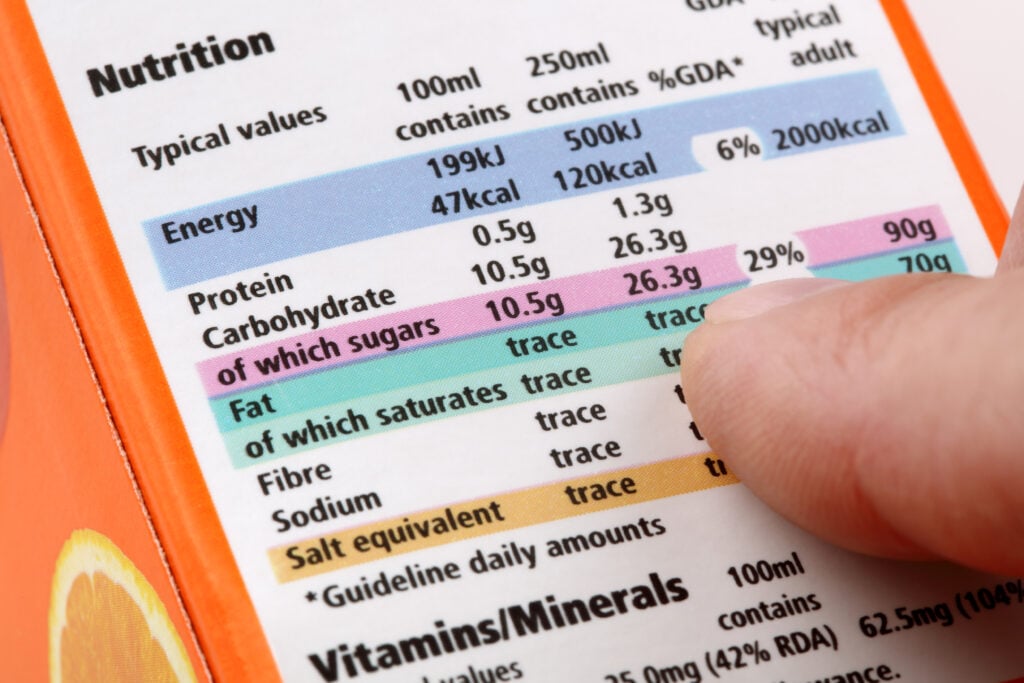

Weighting, and decisions behind it, become ever more important. Also – origins are not the only important issue. Sometimes the intended use case is where the higher duty of care is required. We may want to read the ingredients on a cereal box, but it’s not a matter of life or death. Taking medicine on the other hand, you definitely want to know exactly what the ingredients are. So what are we predicting or generating? The EU regulatory framework for AI discussed below establishes a hierarchy of low or high risk AI use cases. We’ll see more of that.

One part of the industry already groping towards the need for an AIBOM as a business critical issue is commercial open source.There was an interesting post recently by Matt Asay about AI and open source licensing a few days ago – Making sure open source doesn’t fail AI. The argument is that open source licensing had failed in the age of the cloud, and we needed to avoid making the same mistakes. What jumped out at me however was a quote from Stefano Maffulli, executive director of the Open Source Initiative (OSI), which certifies what is, and what is not, open source from a licensing perspective. He said you’d need

“A very detailed description of what went into creating the artifact.”

As Asay writes

“In this world, you’d need to publish all the scripts that went into assembling the data set, the weights that govern the LLM, the biases you bring to the model, etc. This, in my view, is a much more interesting and useful way to think about open source AI, but it’s also far more complicated to deliver in practice.”

Complicated? Absolutely. But increasingly important.

In a really smart tweet Jordan Hamel makes the case that OpenAI is the Napster of the LLM revolution.

OpenAI in some ways is the Napster of AI who learned from its mistakes by getting MSFT on board since they’ve traveled through the legal journey of the underworld and back and have the $$$ to make it legal. A machine learning model that can generate copyright derivative material in a variety of modalities does conflict with existing copyright law and one way or another it’s going to come to a breaking point. Imagine DMCA for your generated content? Napster blew people’s minds in the 90’s for good reason and it took well over a decade for the legal products to exceed its quality and content distribution.

This is spot on. We’ve been shown something incredible, and we want to use it, obviously. The great softening up has begun. And we need an AIBOM from a business perspective. Why? The answer is, as ever, found in governance, risk, and compliance.

Large Language Models (LLMs) could take a wrecking ball to regulated industries. Any regulation that concerns itself with user privacy, for example, is not going to survive first contact with LLMs. The HL7 patient data interoperability standard wasn’t designed with the cloud in mind, let alone AI. Or think about HIPAA, or GDPR even. So enterprises are justifiably concerned about feeding LLMs with user data. In areas such as manufacturing, engineering or polluting industries regulations abhor a black box, but that’s exactly what LLMs are. Copyright infringement is another potential concern – the first class action lawsuits have been lodged by authors against OpenAI.Then of course there is the fear that using public LLMs might lead to security breaches and leakage of trade secrets. Data residency continues to be a thing, and public LLMs are not set up to support that either – if German data needs to be held in a German data center how does that chime with a model running in a US Cloud. And how about prompt injection as an emerging vector for security threats?

So far tech vendors have been remarkably relaxed about these fears, while enterprises have been somewhat less confident. Google and Microsoft have promised to indemnify users if they are challenged on copyright grounds, for example. Their highly paid corporate lawyers are evidently pretty confident that a fair use argument will prevail in court, for outputs from AI models. As ever this is a question about tolerance for risk.

And sometimes the promises about trust don’t stand up to scrutiny. Thus for example Adobe said it’s Firefly image generation model was “commercially safe” because artists had signed up for it – this was [apparently a surprise to some content creators. Adobe, however, has continued pushing its trust credentials with the introduction of a “made by” symbol for digital images, establishing provenance, including, for example, if it was made with AI tools.

The EU is moving towards some far-reaching (some might argue over-reaching) requirements around model-training with its coming EU AI Act

Some notable statements in the positioning document. Considerations of “high risk” (All high-risk AI systems will be assessed before being put on the market and also throughout their lifecycle.)

include:

AI systems that are used in products falling under the EU’s product safety legislation. This includes toys, aviation, cars, medical devices and lifts (elevators).

Meanwhile, here is the copyright kicker.

Publishing summaries of copyrighted data used for training

Perhaps we can just ignore EU law. A lot of folks consider the GDPR to be more of an annoyance than anything else. Facebook can easily afford to pay its $1.3bn fine – that’s just a cost of doing business, right? The US has replied with sabre rattling that regulation will only serve to entrench the major players.

Some companies might feel confident in ignoring EU law – YOLO – but if they want to do business in China, that’s not really an option that’s open. This thread from Matthew Sheehan is essential reading for anyone interested in AI regulation, or the lack of it. Also this post. The TDLR – China is literally years ahead on AI regulation. In China at least:

The draft standard says if you’re building on top of a foundation model, that model must be registered w/ gov. So no building public-facing genAI applications using unregistered foundation models.

So that’s certainly a potential future. China has an AIBOM-like requirement and policies and procedures and corporate responsibilities that go with it. We’re all going to have to think through this stuff – Norway just announced a Minister for Digitalisation and Governance with Responsibility for Artificial Intelligence, Karianna Tung.

According to Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre:

Artificial intelligence offers enormous opportunities, but requires knowledge, management and regulation. Because it must still be the people who determine the development of technology, not the technology that controls the people.

Sentiments that I agree with. And regulation – that’s going to need an AIBOM. Major vendors are talking a lot about trust and AI, and jostling for market positioning accordingly – again, this is where an AIBOM is going to come into play.

disclosure : Adobe is a RedMonk client. OpenAI is not.

Enterprise hits and misses - AI sparks a no-collar work debate, HR tech week gets a critical review, and hybrid work disrupts real estate - TECHTELEGRAPH says:

October 23, 2023 at 11:55 am

[…] Introducing the AI Bill of Materials – RedMonk’s James Governor weighs in on how we’ll arrive at AI project validation (and regulatory compliance): “The AIBOM will need to consider and clarify transparency, reproducibility, accountability and Ethical AI considerations.” […]

Enterprise hits and misses – AI sparks a no-collar work debate, HR tech week gets a critical review, and hybrid work disrupts real estate – diginomica – High-rise Marketplace says:

October 23, 2023 at 12:09 pm

[…] Introducing the AI Bill of Materials – RedMonk’s James Governor weighs in on how we’ll arrive at AI project validation (and regulatory compliance): “The AIBOM will need to consider and clarify transparency, reproducibility, accountability and Ethical AI considerations.” […]