The growth of the Android platform undoubtedly masks some of its shortcomings. As Chris DiBona summarized, “the only thing that really matters is how many of these we ship…There is a linear relationship between the number of phones you ship and the number of developers.”

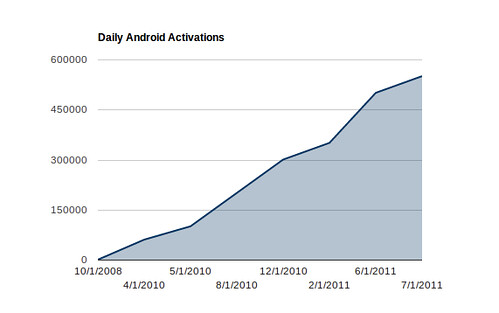

Assuming shipping volume is the metric of success, this hypothesis has been correct thus far. Regardless of what one thinks about Android the platform or its various hardware instantiations, what’s not arguable is that it is a success as measured by volume. The question for Google, Android developers and competitive platforms is whether this is sustainable, or if there are cracks in the foundation that will slow the above trajectory moving forward.

Here’s what would concern me about Android if I worked for Google:

Clustering of Handsets

For the coming holiday season, Android has several new handsets that are certain to be positioned as legitimate iPhone 4S competitors: the Samsung manufactured Galaxy Nexus, the Motorola Droid RAZR and the HTC Rezound. Besides being Android vehicles, all of these handsets have one thing in common: they’re all being released on Verizon.

Granting that Verizon is the largest carrier in the US, the merits of this strategy seem questionable if the goal is maximizing the addressable market for Android. One or more should have been simultaneously shipped on AT&T, the second largest network, or at least on second tier players like T-Mobile or Sprint.

It may yet come to pass that one or more of these handsets ship on a carrier competitive with Verizon – details of carrier coverage and availability have been scarce, itself an issue – but time is a factor during a busy holiday season.

The limitations of this handset clustering must be obvious to Google, which means that either they are unable to exert sufficient control over the manufacturers and carriers to maximize their penetration, or that the carriers have incented Google sufficiently financially to make a tactical sacrifice.

Neither possibility is encouraging, for Google or users of the Android platform.

Fragmentation

Google’s attitude towards fragmentation has been consistently dismissive; top to bottom, the organization has been willing to trade API consistency and compatibility for rate of innovation. And as discussed above, this strategy has been successful.

That said, as the platform iterates the versioning and thus fragmentation challenges multiply. Michael DeGusta visually depicted the challenges Android developers and users face with respect to fragmentation.

This problem can only be expected to get worse, as versions proliferate and the carriers who are incented to not update their users remain responsible for operating system distribution. Amazon’s effective fork of Android, which will underpin its Kindle Fire tablets, is likely to further complicate an already problematic developer story.

Google’s promised solution to this problem, meanwhile, has yet to show material benefits.

Patent Issues

Google is obviously not responsible for our fundamentally broken patent system [coverage], and it is to their credit that they have been as publicly outspoken against patents as they have. But their historical lack of focus on intellectual property accumulation has proven to be, in retrospect, a mistake. Fair or unfair, the current patent system is the current market reality. Worse, there is little evidence that we will see a solution within the projectable future, but substantial reason to believe otherwise.

While Google has employed a variety of mechanisms to address this strategic shortcoming – from discrete patent purchases to accumulation by acquisition to combat via partners – the perception is that they are losing. Building the case otherwise is challenging with the Microsoft claim that over half of Android OEMs are paying an intellectual property tax to Microsoft.

Android is far from the only player to have patent issues in mobile, to be sure, as this graphic indicates. But they may have the most to lose.

Tablet Application Volume

When the Xoom launched, the Android Market contained a mere 16 tablet specific applications. According to market.android.com, in the eight months since, they’ve added 150 new tablet applications, yielding a growth rate of 940%. Which sounds positive until you realize that the iPad more than doubled its 65,000 application catalog, which is now 140,000+ strong.

To some extent, this is unsurprising. Application generation is typically a function of adoption; as DiBona asserted above, there is a linear relationship between hardware shipments and developer interest. With Android tablet shipments anemic at present, in spite of Google’s efforts to seed the markets at events like I/O, developer interest could be expected to lag.

What is curious, however, is Google’s inability or unwillingness to get key, flagship applications ported to the platform. Nearly three quarters of a year after the official release, there is still no tablet-optimized official Twitter client. Ditto for Facebook, although they were inexplicably late to market with their iPad offering. MLB initially promised a tablet optimized version of their At Bat application similar to what was available for the iPad, but never delivered it.

So while Android has had notable wins like the NFL ’11 application for the tablet form factor, it remains tens of thousands of applications from being competitive from an applications perspective. The question is why?

Apart from the obvious answer in hardware volume, some of the explanation may lie in developer trepidation around the nature of the Honeycomb platform. With Google admitting that it took shortcuts to get Honeycomb to market in time, some developers may have chosen to wait for the unified Ice Cream Sandwich platform. But it remains curious that Google hasn’t been able to incent – financially or otherwise – key application partners to make the platform more compelling to users and potential developers.

With application availability proving to be crucial to the iPad’s ongoing success, it will be critical that Google resource itself appopriately to remedy this issue.