Cloud Camp, in case you’d missed it, is tonight. The usual suspects – and a few unusual – will be in attendance for what promises to be an interesting evening.

Personally, I would being going if I had managed to swing a trip to San Francisco this evening, but there was no joy on that front. Sadly, having been seriously out of the office more or less the entirety of last week, I won’t be in attendance (though my colleague will, so look for him).

But let me toss a question out for the attendees to consider, if they happen to be so inclined: when will standards arrive, and who will be driving them?

The answer to the latter question is more predictable, of course: standards are nearly always driven by market laggards (as an aside, I highly recommend Stephe Walli’s standards primer – excellent educational work from someone whose lived the standards battles). And so it might be expected in the burgeoning but still nascent cloud computing market. But there are de jure standards, and there are de facto standards, as the office productivity players are intimately familiar with after all these years.

And based on the offerings to date – or rather, the lack of same – it seems apparent to me that major would be cloud players have yet to digest the potential for the incumbents to achieve de facto status. It’s arguable, in fact, that with players from CohesiveFT to Elastra to Enomaly to Red Hat targeting Amazon’s EC2, we could see AMI’s quietly become the cloud standard sans fanfare. Which, as any of the non-VMWare virtualization players may tell you, is suboptimal for the non-originator of said standard.

The question of standarization is, I believe, an important one because the most important metric for cloud services might well be control. Or choice, if you prefer. As Simon Phipps once famously declared, “it takes full substitutability for me to have the confidence to stay as well as the freedom to leave.”

As yet, there is no real Freedom to Leave to be found in the cloud. I could move an application from Google App Engine to Amazon, perhaps, but not easily. And Salesforce.com’s Force.com takes that even further, as Cote observed during his time yesterday. Here’s how I contrasted a handful of the would be cloud providers approaches in discussing the launch of Google’s App Engine:

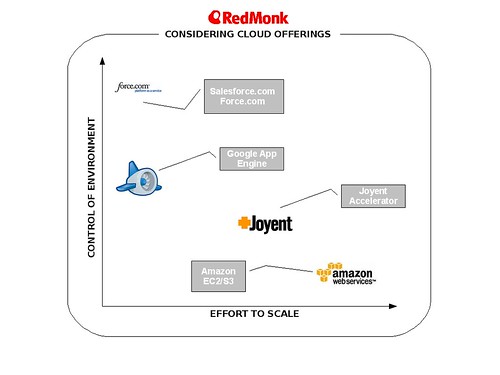

If we think of cloud computing offerings on a spectrum of closed to open, with Salesforce.com’s Force.com on the closed end and Amazon’s EC2/S3 at the open (though the Joyent guys can credibly argue to be more open than Amazon), Google’s App Engine is somewhere near the midpoint. It does impose a proprietary database (Bigtable) on would-be developers, as does Force.com, but it allows for the use of a standard programming language (Python) rather than the proprietary one required of Force.com developers. It’s more constrained than Amazon, of course, which essentially offers developers the freedom to pick and choose from the bare metal of a virtualized platform on up, but Google’s approach does offer some advantages to with its disadvantages.

Or, for those of you that are more graphically inclined (clearly more so than myself, as the primitive nature of the graphic attests), here are a few of the cloud providers portrayed in simple fashion visually along the dual axises of control and effort to scale.

The fundamental differences in approach – Amazon chooses virtually nothing for you, Joyent the operating system, Google the programming language (non-proprietary), operating system and database, Force.com the os, database and language (proprietary) – would seem to preclude easy or efficient standardization. And yet it will arrive, if only because customers will demand it. When the overwhelming deployment paradigm of the age is application on top of database on top of general purpose operating system on top of commodity hardware, it would seem difficult to convince the late or mainstream adopters that the entirety of that approach is wrong.

Which leaves the question of who will seize the opportunity that remains: standardizing cloud platforms such that migration – live or otherwise – becomes possible. Technically, the tools are there, as virtualization providers prove daily. The business justification may prove more difficult, with the current stable of cloud vendors perhaps too enamored of Shapiro and Varian’s switching cost to net present value equation.

That standardization will, in spite of that, occur, seems inevitable to me. Who will seize the opportunity and when, to me, are the real questions, and it just might be that the answer is to be found at Cloud Camp. I’ll certainly be watching as an analyst, but also as a customer.

Disclosure: Of the mentioned vendors, only Red Hat is a client.

Recent Comments