Preface: What follows is a rather long essay that is outside the bounds of what I normally cover; I print it here first because I wouldn’t know where else to post it, and second because the issue concerns me deeply. The entry discusses the frustration that I have with the notion of ‘certainty’ in general, with some exploration of the technology specific implications of faith. I’ll warn you up front that the entry is long, not particularly relevant to my normal coverage, and may make some of you uncomfortable. Like the Adam Bosworth post mentioned below, this is an entry that’s been in the works for some time. With that opening, I’ll leave the decision as to whether or not to continue up to you.

Main: Once upon a time, when I was nothing but a wee lad growing up on the mean streets of suburban New Jersey [1], my parents – like just about everyone else in our sports crazed town – took a page straight from the Pharaohs of Egypt playbook in order to deal with the problem of their children’s free time. The Pharoahs, you see, figured out pretty quickly that idle hands are indeed the devil’s playthings, and after much experimentation they came up with a simple solution that even the folks from lesscode.org could be proud of: ensure that there were no idle hands by putting everyone to work creating the pyramids. Simplicity itself. The fact that it involved enslaving a significant portion of the total population was regrettable, but preferable to outright chaos and revolt. Or would be, presumably, if you didn’t happen to be one of the slaves.

Fortunately for myself and my friends, our lot growing up was not hauling five-ton blocks of Egyptian sandstone around for the entirety of our natural lives, but rather the slightly less taxing endeavor of team sports. Even for one towards the less talented end of the athletic spectrum such as myself, this was fortuitous. The actual sports I participated in varied over the years – soccer, basketball, baseball, and lacrosse in my elementary school days, subsequently whittled down to just football and lacrosse in high school and college. In terms of their rules, required skillsets and relative degrees of difficulty, these sports had little if anything in common. There was, however, one thread that united them – one shared activity that varied little from soccer practice to basketball practice to to lacrosse practice to football practice: calisthenics.

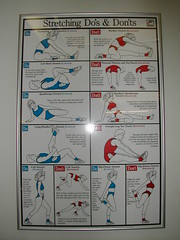

Most of the folks reading this have probably experienced these stretching exercises at one time or another, even if it was just in phys ed class. Stretch your quads, stretch your achilles, etc. But while working out at the gym here in my building about a week ago, I happened to glance at the chart that’s inset above. It’s not the typical thing I’d stop and read, because having been playing one sport or another for the better part of my life to date, I know how to get ready for physical activity (even if I’m less capable of it than I once was). I certainly don’t need a chart to tell me how.

But for some reason – maybe it was just that I was tired and needed a breather – I stopped and took a few seconds to read through the chart. In doing so, I noticed something quite surprising, at least as far as I was concerned. Of the variety of stretching exercises I was trained to perform – probably at some point in the first or second grade – and have dutifully repeated ever since (or at least pretended to – I was never a big fan of stretching), pretty much everything I was taught was wrong. According to this seemingly omniscient chart, every last exercise that I followed from first grade soccer practice all the way through adult winter snow football on Shadow Mountain Reservoir two winters ago was on the wrong side of the “Do’s / Don’ts” divide.

Many of you are probably less than shocked by this, given that our understanding of training regimens has made more than a few advances in the last 30 years, but for me it triggered a minor epiphany: much of what we know, is in fact wrong. From biology to gym to history, a substantial portion of what we are taught in our formative years is just plain incorrect. Some of the errors are intentional, some are not, but it’s impossible to argue that pretty much all of us are force fed large quantities of faulty data. Nor are the inconsistencies limited to education; how many times, for example, have health professionals changed their minds on whether or not eggs are healthy or unhealthy? First they’re good, then they’re bad, now, well, now I don’t even know if they’re good or bad, I eat them anyway. I’m sure each of you could come up with your own examples; when discussing this topic with a friend recently, they were immediately reminded of the very checkered history of medicine. Actively bleeding patients, after all, was a recommended and ardently believed in treatment for a variety of ailments well into the last century.

If it was human nature to recognize and accept that our understanding of the world around us is at best imperfect and at worst hugely flawed, one suspects this might be less of a problem. But unless what you see in the news is a hell of a different than what I get every day on Google News, that’s not the case. People all over the world are murdered every day because of what someone “knows.” Most of us blindly cling to the things “we know,” because the alternative is too difficult to accept. Change, after all, is always bad.

In the movie Men in Black, which in and of itself is not a bad film but hardly profound, Tommy Lee Jones’ character explains this aspect of human nature to Will Smith with the following statement: “1500 years ago, everybody knew the earth was the center of the universe. 500 years ago, everybody knew the earth was flat and 10 minutes ago, you knew the human species was alone on this planet. Imagine what you’ll know tomorrow.” The quote, if you’ve seen the movie, does not do justice to the emphasis placed on the repetition of “knew.” Knowing, the statement in implies, is as much an aspiration as it is a fact – perhaps more so.

In one of the more important – and controversial – entries I’ve read in a long time, Adam Bosworth passionately decried the victory of faith over facts that is increasingly visible in the world today. While Adam chose to spend time on the implications of faith with respect to non-verifiable belief systems – i.e. religions – that’s not my principle worry. It’s not that I don’t share his concerns – I do, and it’s not that it’s a problem that one has to look very far to find. I defy anyone to read Krakauer’s account of the actions of the Mormon Fundamentalist Lafferty brothers in 1984 and not emerge profoundly concerned about the often violent implications of faith. The power of faith, just we’ve seen with the power of nationalism in my country of origin, can be as wrong as it is right.

But while I lend my single voice to Adam’s plea, that’s not a problem that I can solve. Nor would I ever suggest that religions have not done wonderful things on an individual or group basis. When one of my close friends passed away just short of a year ago, I witnessed first hand just how profound an impact his family’s faith had on their grieving process. No, it’s not my place to judge beliefs, whatever they might happen to be; if I was, I’d be guilty of that which I fear most – being too certain that my own beliefs are in some way more correct than those I observe. But what does deeply, deeply concern me is when faith obscures the facts, when conviction overturns reason, and when individuals blindly follow an agenda without stopping to think – might I be wrong?

The implications of misguided faith need not be as dire as the crimes committed by the Lafferty brothers; often it simply leads to unpredictable, even humorous, behaviors. One wonders, for example, whether it might not benefit some of the members of the Melanesian Cargo Cults that Feynman discussed to dedicate their lives to something other than constructing makeshift airstrips, airports and radios out of straw and coconuts in the hopes of luring cargo planes.

By now you’re probably asking yourself: what in the hell does any of this have to do with technology? Am I reading the right blog? But as it turns out, this type of unassailable conviction – the offlining of essential, critical thought processes – is all too common in our little tech corner of the world.

As Lessig covers, Jack Valenti knew that the technology of cable television would become a “huge parasite in the marketplace,” just as he knew that “the VCR is to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston strangler is to the woman home alone.” The composer John Philips Sousa was likewise convinced that the advent of devices like the player piano would “ruin the artistic development of music in this country.” And the list goes on and on.

For examples closer to home, one merely has to speak with the extremes of any of the developer populations: J2EE zealots will look down their nose at PHP and call it a toy, while the PHP faithful will respond by calling Java bloated and a dinosaur. For their part, many in the .NET crowd are convinced that both of the former groups are missing out on the one, true development tool – Visual Studio. Or take the web services strife; those in the REST camp have no time for the WS-* folks, and vice versa. And those discussions are nothing compared to what we’ve seen with the rise of open source, with commercial vendors playing the Inquisitors to the F/OSS community’s Cathars.

The problem, I submit, is not necessarily in the opinions themselves. Competition will almost inevitably give rise to such invectives, and competition generally speaking is a net positive. No, the problem is rather the degree of conviction – the inability to take that step back, evaluate a given argument thoughtfully, rationally, and – should worst come to worst – concede a point lost. Many of the folks from the examples above “know” that they are right, and that their chosen approach is the one, true approach. Never mind that many of the minds that thought that the earth was the center of the universe or that the world was flat were good ones; the technology industry seems to breed fundamentalists like flies. Many of the folks in this industry manage to convince themselves that their technology is somehow the equivalent of the stone tablets come down from Mount Sinai.

Well, I don’t know about you, but I’m tired of it – just plain tired of it. Like John Stewart during his magnificient appearance on CNN’s Crossfire last year, I just want to say please stop – you’re only hurting yourselves. In the afterword to what is an otherwise terrible novel, The State of Fear, Michael Chrichton makes the following statement: “I am certain that there is too much certainty in the world.” If there’s one thing that I personally am certain of, it’s that that statement is correct. I don’t care what you choose to believe – technically or otherwise, but I do care when you consider your beliefs infallible.

Let’s take Microsoft’s Jason Matusow as an example. There are things – a great many things – that he and I are never going to agree on. Some of these are subjects that I care deeply and passionately about, and yet I have immense respect for him personally and professionally. Why? Because he’s not a fundamentalist; rather than merely serve as a mouthpiece for the Microsoft attitudes towards open source as of ’99/’00, he chose to educate himself on the subject, and in doing so has educated his employer. How much easier would it have been to merely regurgitate lines like “open source is a cancer?” Instead, Jason made the difficult choice of rationalism and facts over what was “known” about open source within Microsoft at that time – and for that, I believe, he deserves your respect, as he has mine.

According to Wikipedia,[2] Thomas Aquinas was the first to put foward the notion of a tabula rasa, while John Locke was the one to take that and run with it. Locke’s philosophy was that the human mind at birth is an empty vessel that is shaped by the choices the individual makes. As Wikipedia notes, however, the modern usage of term is less focused on the individual, and more on the impact of environment on an individuals development, and it is in that sense that I use it. While I accept as likely that there are in fact some traits that most of us are hardwired with – that which we might term human nature – I otherwise lean towards the latter view that we are very much the product of the experiences, teachings, and shared wisdom of one’s particular culture.

If one accepts that position, one must then ascribe a great deal of importance to our education – whether that’s in an academic, cultural or religious sense. Personally, I don’t believe this to be inherently bad or good – it just is. What I find dangerous, however, is when this education is prematurely halted or bent towards particular ends, and we lose the ability to question, to doubt, and to reason.

If there’s one thing that I hope that those of you still with me take from this entry – what has effectively become an overlong screed against the perils of blind faith – it’s simply this: of everything that you know is right and true, only some is. The point here is not that convictions are a bad thing, but rather that it’s critical to know when to look at them with a critical eye. Question everything.

[1] You read that right – I am indeed from NJ, not Boston as most people tend to assume.

[2] Wikipedia is in itself often a victim of individual ‘certainties.’ Critics of the community driven encyclopedia often point to the errors in individual entries as proof that it has no merit. While this criticism is often well founded, it overlooks the assumption (erroneous, IMO) that competing sources are somehow immune from this flaw. The fact is that even history books covering a particular subject in detail are subject to their own errors, not to mention the selective employment of ‘facts.’ In short, is Wikipedia flawed? Absolutely. But show me a source that is not, and at least I can fix Wikipedia.

Recent Comments