This is part of a series on publishing (in academia and/or tech).

A Victorianist friend once stated that she loved the quaint practice among medievalists (those of us who study the Middle Ages) of celebrating our colleagues through festschrifts: collections of critical or reflective writing honoring the contributions made by an individual over the course of their career. Such collections are often presented to the honoree at an important milestone (such as retirement). While “festival script” might be a closer cognate of the German, I prefer to think of festschrifts as “celebration writing”, or ways to leverage the written form to honor people whose writing has made a mark on our world.

Here at the end of 2023, a time that juxtaposes seasonal celebration with reflections of a year of global conflict, tech layoffs, and general uncertainty, I find myself contemplating this concept of celebration writing, both as a genre and a larger philosophy of writing. This pensiveness arises in part because, as I have written, 2023 has felt like a year of losses, and festschrifts as a genre–in contrast to tributes in memoriam–ask us to honor people while they are still with us. But I suspect that another part of this is driven by an impulse to reflect on the aspects of writing–an act that feels particularly in a state of flux–that make it suited to such celebratory acts. So please also consider this a celebration of celebration writing.

But first thing’s first: some more on festschrifts.

If this is your first time hearing the word “festschrift” you are not alone. Even among academics, the term feels old school, as demonstrated by the above anecdote of a Victorianist–a scholar who studies a period that ended over a century ago–referring to the practice as “quaint” (and indeed, the OED traces the word’s usage in English back to the nineteenth century). Festschrifts can include writing from current and former colleagues and students/mentees, and said contributions usually directly address or build on the honoree’s prior work. For instance, a recent festschrift for Dr. Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe, my undergraduate advisor (who, when we were both at Notre Dame, taught one of my favorite courses, which required us to read Beowulf in the original Old English) includes a mix of new critical essays on early medieval textuality and subjectivity as well as an overview of her expertise in this area. It is also worth noting that the volume employs an “Essays in Honor of” subtitle–a common way to denote a festschrift without using the word per se.

Prior to the wide availability of digital formats, festschrifts would often take the form of a hardcopy volume of essays, a copy of which would be physically presented to the honoree at an in-person event. Such events can be organized to coincide with a professional conference–and I recall quite a few taking place during my once annual trips to the International Congress on Medieval Studies. These days, of course, there are a variety of digital formats that can be leveraged for festschrifts, sometimes in what feels like poetic ways. When medieval art historian Dr. Rachel Dressler retired, Different Visions, the online open access journal that she founded devoted an entire issue to celebrating her work, and with the forward-looking caveat of “Though this issue is inspired by past accomplishments, it looks resolutely to the present and future of medieval art history.” As Dr. Dressler was on my dissertation committee, I had the privilege of contributing an article to the issue that reflects on how her work and mentorship helped shape my own way of looking at the world.

While festschrifts are a common format among medievalists (at least those from my generation and earlier), a quick look at the history of the term (and wikipedia has a workable one if you don’t want have OED access) reveals that the genre is not just a medievalist thing or even a humanities thing, and may be even more common in STEM fields. My research into festschrifts turned up an article with directions on how to “Prepare A Festschrift” from the British Medical Journal and a piece on the festschrift genre from life sciences magazine The Scientist. If you want examples that are more recent (and at least as science-y), check out this 2022 issue of The Journal of Chemical Education and this 2021 issue of Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. And in case you missed it, these last two directly use the word “festschrift” in the issue titles (i.e., no flowery “essays in honor of” language here).

It is worth noting that certain aspects of the genre can be problematic. Who a festschrift honors (and for what) can sometimes reproduce patterns of recognition and exclusion that we’ve seen play out in the academy and tech industry alike. The practice of “surprising” honorees with such efforts can also lead to mixed results (and indeed not everyone is comfortable being the center of such attention). Furthermore, as editorial projects and published scholarship, festschrifts constitute a category that some institutions will (while others will not) recognize as scholarship when making hiring and promotion decisions. As such, they are often characterized as “labors of love”, and yet even then the practice raises questions of who takes on the labor involved in putting such a volume together or producing (or modifying) a contribution.

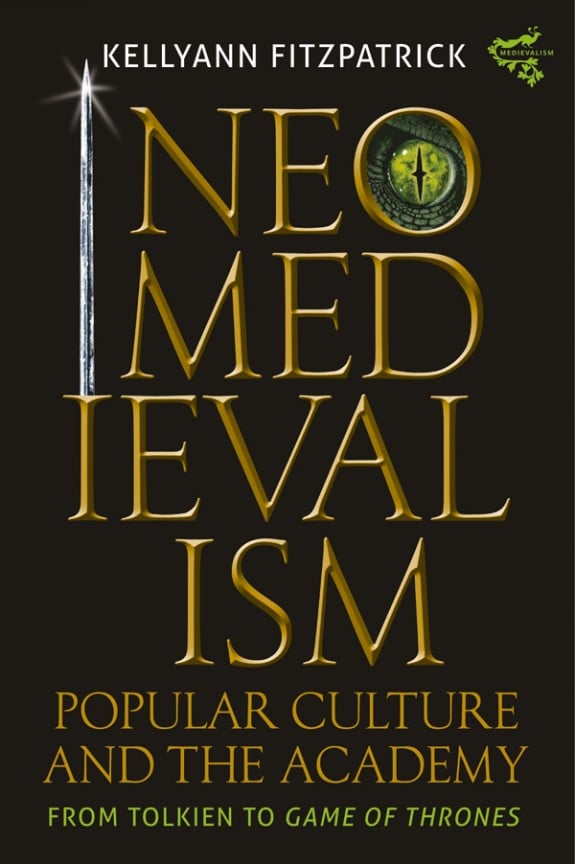

And yet, even with these concerns, I still say there is a case to be made for celebration writing, even beyond the confines of a formal academic festschrift. Looking back over my own writing in the past few years–the pieces that have given me the most joy are those that celebrate people and/or their accomplishments. The article for Rachel Dressler’s festschrift was tricky in that I had to carve out time amidst the many other demands on my schedule, but it was also an absolute joy to write. Even among my RedMonk writing, I think back most fondly on pieces I wrote to celebrate the publication of books on illustration and fencing, to enthusiastically welcome a new colleague or two, and to chronicle the people and events that helped make RedMonk what it is today. Notably the last of these also catalogs a #20YearsOfRedMonk social media celebration that had a very festschrift-ish feel, which made me realize that the tech industry might have its own take on celebration writing.

Such writing also represents a gift of time, effort, and thought that feels all the more valuable when many writing tasks are purportedly being relegated to AI-based tools. That is not to say that such tools have no place in celebration writing (and how long until we get our first prompt engineered festschrift?). While I do think artisanally crafted celebration writing may signify differently–both to writers and to honorees–than whatever genAI can currently cook up, I suspect that recognizing and celebrating the people whose work means something to us is a worthwhile effort regardless of the tools and formats used.

To that end, if you have any examples of celebration writing that you’d like to share (especially those related to tech), I’d love to know.

No Comments