Dr. Eli Thorkelson—PhD in anthropology, software engineer at Workday, and a former coworker of mine from my first job in tech—joined me for a recent episode of the Docs are In. Beyond our work history, one thing that connects Thorkelson and I is our shared academic background. Improbable as it seems, when we worked on a small team of 7 engineers, 2 could boast PhDs. Unreal. Clearly I still haven’t come to terms with this coincidence, so I invited her to help me process what it means to hold a PhD in the social sciences and humanities (my own PhD is in literary and cultural studies), and then reskill into the tech field.

I am perennially curious about how skills translate from academia to the tech industry. Although humanities majors are frequently assured that the competencies they acquire as part of their course work are desirable in business, I can say from experience that they do not automatically result in job offers. To be sure, skills like communication, leadership, public speaking, and attention to detail are desirable qualities in the software industry. But these so-called soft skills need to be complemented by deep technical expertise. For software engineers there is no getting around the fact that the reskilling process requires an understanding of complex systems. And yet, according to Thorkelson, soft skills (my words, not hers) really are the ones that carry over the most meaningfully from academia. As Thorkelson explains:

I think that what you get out of doing a PhD in social research like in Ethnography or something like I have, is that you prioritize relationships and communication. And let’s be honest, that is something that is a variable interest to professional technology people.

If this is the case, I find it all the more remarkable that so many academics who have never studied technology in a formal setting, have chosen to reskill into tech roles. Or is it? For Thorkelson, the conventional biography of an academic-turned-developer is reversed. She was already a paid software engineer before coming to academia:

I was a teenager in the 90s, at a time when there was a lot of early Internet culture happening and a lot of programming nerd culture happening, which I loved. And I was really into that stuff as a teenager, but I really didn’t like computer science, formal education … So I didn’t get any degrees in computer science. And I found out pretty quickly — I think I was 19 the first time someone paid me money to write code and I kind of said to myself, I don’t need to study CS indefinitely since the jobs are kind of there already if you’re able to produce working software

It is more accurate to frame Thorkelsen’s move into tech as a return. Her talent for software development emerged from her long standing fascination with computers. She is a tinkerer with broad interests and abilities. Which makes her history of committing to PhD studies, and eventually leaving the academy, all the more compelling.

Thorkelson articulates her feelings about transitioning out of academia possibly better than anyone I know. Her story, which intersects with the genre of “quit lit,” does not hinge so much on how she reskilled, but rather why she elected not to pursue a career in higher education and what the process of severing this part of her identity looks like. For those unfamiliar, “Quit lit” is an established genre among former academics, which Lukas Moe explains comes out of a general interest in the decline of the academic profession:

To the outside observer, academics are a confounding case. Why spend years earning a graduate degree whose professional paths forward are so few and narrow? Like Odysseus strapped to the mast, academics seek enlightenment in the siren’s call of that ultimate labor of love, the vocation, while drifting toward the rocks of precarity.

…

As conditions deteriorate, and the call of vocation grows harder to hear, academics have written more about work. The confessional strains of this literature belong to the subgenre of “quit lit,” which ranges from bitter anguish to wrenching grief. I would say quit lit should be shelved next to adjunct lit, but its market is coterie at best. Whereas failing at a career is an age-old theme, only so many pages can be turned with vicarious sympathy for someone quitting or deciding to quit. Miserable protagonists and narrators are fashionable, but there is no frisson of autofiction in quit lit. What happens instead is slow and wrenching and sad.

Decasia, Thorkelson’s blog, fits the remit of quit lit, but in a manner that reflects her identity as a software engineering professional. I find her post “Unbecoming an Anthropologist” particularly moving. In it she explores the emotional aspects of abandoning an academic career, as well as the process of mourning that follows. The whole post is worth reading, but this section is particularly poetic:

Unbecoming an anthropologist: You stop trying to speak in a certain tone, the academic tone of voice. That tone starts to seem thorny and stilted, though it used to feel natural and empowering. It stops making you feel like you are part of something.

Unbecoming an anthropologist: Your existence no longer hinges on your knowledge, your thoughtfulness, your capacity to theorize. You will no longer make cultural analysis into a cornerstone of your professional being in the world.

Unbecoming an anthropologist: Above all, you cease to constantly REPEAT the little ritual incantations that held up your claims to “be” that thing. To “be an anthropologist” involves constantly DECLARING your identity as if it were the most obvious thing in the world. “I’m an anthropologist…”, “I’m in anthropology…”, “As an anthropologist…”

The decision to leave academia to pursue a career in industry is complicated. Academics tie so much of their identity to this profession that it often requires a significant break for them to see themselves as anything else. Without this structuring way of moving in the world, former academics must reinvent themselves: in Thorkelson’s case through “unbecoming.”

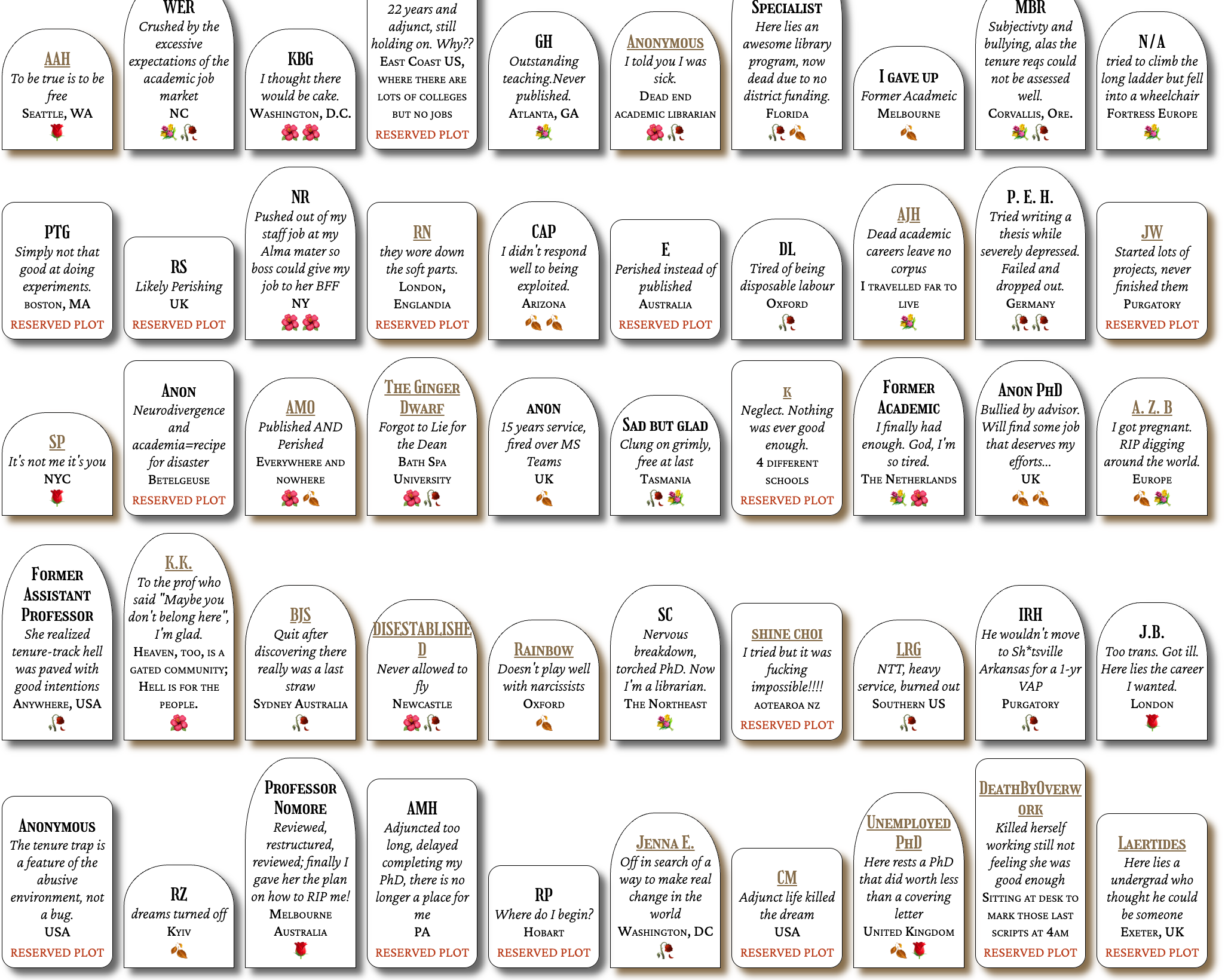

I’ll close out this post with a summary of my favorite project from Thorkelson’s quit oeuvre, which might be called a ‘quit app’ entitled “RIP My Academic Career.” In Thorkelson’s own words, this project is:

a graveyard for careers that didn’t work out in academia. And each time each person who cares to create a little marker for themselves can have a little virtual grave for the career with virtual flowers randomly generated on many of the bottoms of their virtual tombstones. And everyone can write their own epitaph, which I guess is democratic or something. It’s funny because it’s parody and it’s not, you know, like I don’t really — and I think that there was interest…And so I won’t say that people only used it in healthy ways, but for the most part I think that it seemed like it found its audience who felt peace with it

As a former Victorianist I relish any opportunity to reflect on funerary subject matter. But I am additionally impressed by this project’s penetrating wit. By allowing users to create tombstones for their abandoned academic careers, Thorkelson uses her programming skills to address an occupational tragedy. This humorously morbid app acknowledges the realities and emotions involved in leaving university life. Although many folks outside of academia that I have spoken with about the sadness of abandoning this career tend to want to downplay it because, they assure me, it’s just a job, those who once aspired to a professorial career understand that the break represents a sort of death. Thorkelson’s app makes a profound statement by inviting strangers to place private, pithy gravestone epitaphs in a public, digital cemetery where each marker is accompanied of hundreds of others memorializing the same decision, albeit made for the unique reasons of each individual author. By providing a space for ex-academics to commemorate a difficult decision with a light touch, “RIP My Academic Career” repackages and reinterprets an impossible choice.

If you want to watch my conversation with Dr. Eli Thorkelson you can access it below.

Image credit: Dall-E2

Disclosure: Workday is not currently a RedMonk client.

No Comments