In recent years, funding for AI has been a spigot opened wide. Investors threw money at startups in the space, even more money at those providing hardware for those startups and boards the world over directed their enterprises to embrace AI first and ask questions later.

Recently, however, the economics of the space are facing increasing and unprecedented scrutiny. Enterprises, for their part, have transitioned from a FOMO era to an ROI era as my colleague has captured here. Investors, meanwhile, are beginning to question the circular and potentially problematic deals in the space – see recent pieces from Bloomberg or the Financial Times.

From the latter:

OpenAI has signed about $1tn in deals this year for computing power to run its artificial intelligence models, commitments that dwarf its revenue and raise questions about how it can fund them.

AI, then, is facing headwinds it has not experienced in this generation of adoption. Headwinds which make it imperative that it immediately demonstrates utility and returns to justify the investments. One of the important questions, then, is utility and returns for whom?

Over-generalizing, there are two technology markets: consumer and business. Both markets can produce enormously profitable companies; Apple makes a fortune selling to consumers and NVIDIA does the same selling to businesses. Obviously it’s not that black and white, and there’s crossover and bleed between these categories. Some companies successfully sell to both, but typically companies are built to sell to one or the other because they are very different markets. The marketing and sales motions for each are entirely distinct, the pricepoints and volumes sold differ wildly as do expectations.

This is relevant for AI because to date, while enterprises have poured money into AI in other categories, the largest models outside of the hyperscalers like Amazon, Google and Microsoft have traditionally been consumer focused. OpenAI’s ChatGPT, for example, is famously the fastest growing consumer product in history.

Historically, that type of growth and usage would be the foundation to a solid, growing business even at modest price points. Google, for one, built an enormous business on large volumes of micro-monetization via advertising at an unprecedented scale. For OpenAI and its peers, however, the consumer business – even at wide scale – is unlikely to be enough to either justify the current valuations or meet its incredible spending commitments. Per the FT piece above:

“OpenAI is in no position to make any of these commitments,” said Gil Luria, analyst at DA Davidson, who added it could lose about $10bn this year.

Even if that estimate is off by a factor of ten, it’s clear that for OpenAI and many of its peers, steep costs are not currently being offset by revenues from the consumer sector.

Which brings us to the business sector, and more specifically, the enterprise. Unlike consumers, enterprises have much less price sensitivity. Whether AI has the ability to increase revenues via new lines of business, decrease costs via increased efficiency or both, the appetite for AI within the enterprise – even with some newfound attention on ROI – is clear. But enterprises, as mentioned, are a fundamentally different target than consumers. And this is particularly true for AI.

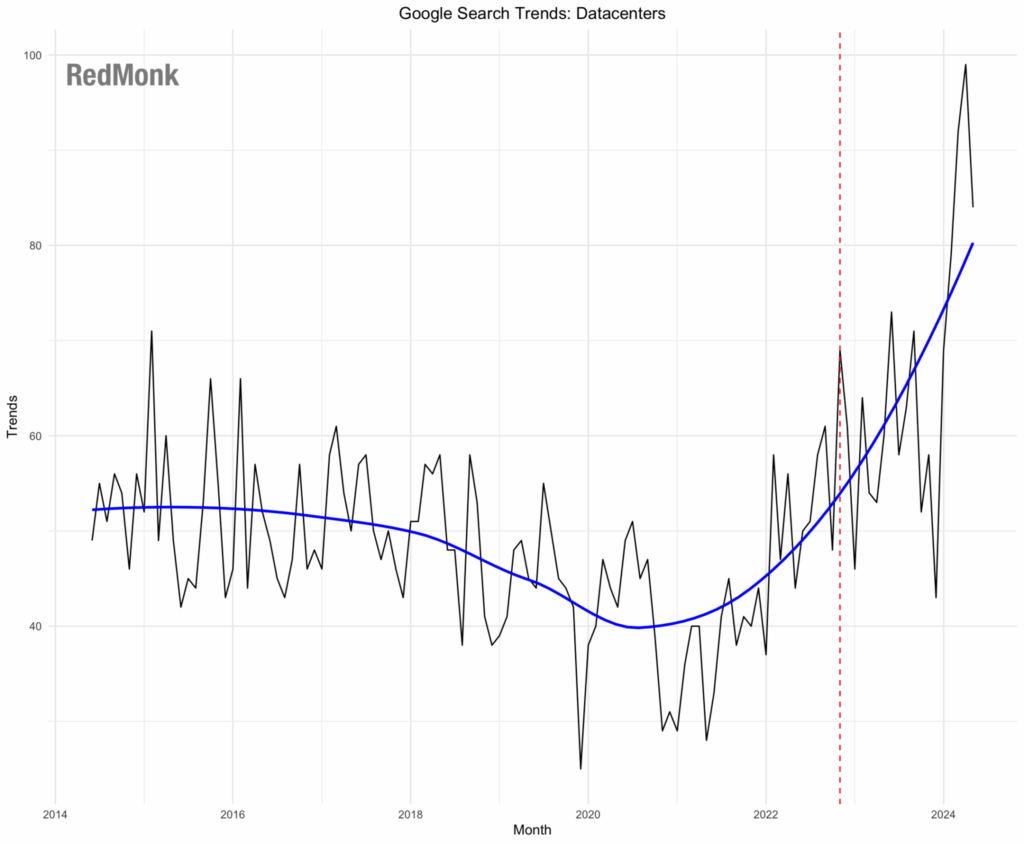

Unlike traditional technology infrastructure like servers, storage, databases and so on, AI has serious trust barriers to be overcome. If an enterprise purchases a commercial database, or even effectively rents one as a service, it has a clear expectation of privacy because a database company has no fundamental interest in the data stored within. AI providers, however, have an insatiable appetite for data wherever they can get it, which creates at a minimum the perception of a conflict of interest. Despite assurances from AI vendors that they will not train their models on user data, a trust gap remains. Google search trends data shows a spike in “datacenter” queries shortly after the release of ChatGPT. That seems unlikely to be a coincidence.

Beyond the trust gap, there are many more prosaic challenges facing would be entrants to the enterprise market. Do you have an enterprise salesforce? Are you on the approved supplier lists for large businesses? Have your products cleared legal and compliance reviews? Do you have a global on the ground presence to chase leads worldwide?

Recently, one highly profitable trading firm RedMonk has contact with attempted to engage with an AI code assist vendor with the intention of paying them a substantial amount of money. Several initial inquiries went unattended, when a reply was finally received and the vendor understood there were questions about compliance and security, they went dark once again. Enterprises tend to not appreciate that kind of behavior.

With that context, there are two obvious questions. First, if you were an AI provider, how would you try to enter the enterprise market? Second, if you had access to the enterprise market with existing model capabilities, but lacked at least a perceived in house top of the line model, how would you make up that deficiency? The answer at TechXchange this week, as it was once upon a time with Microsoft and OpenAI, was a partnership, specifically Anthropic – creators of the well regarded frontier model Claude – and IBM, an arbiter of what technologies to trust for enterprises for over a century.

Partnerships, like any relationship, are only worth the energy that is invested in them. And while the optics of this one were curious, not only with the Anthropic CEO declining to attend TechXchange in person as is custom with major partnerships, but having the requisite video shot in San Francisco rather than New York, the opportunity in front of both parties is clear.

IBM’s – and its subsidiary Red Hat’s – internal AI focus is clearly on small to medium sized models that are lighter weight, cheaper to run and more easily tailored to the types of discreet, specific problems enterprises are looking to solve. The 4.0 Granite models announced at this event speak to that aim, being positioned not around state of the art capabilities, but – potentially more important in the current climate – a blend of reasonable capability, performance and cost effectiveness. For some IBM clients, however, it will be important to be able to tick a box that says “frontier AI model capability,” hence the importance of the Anthropic announcement and the potentially related subsequent bounce in its stock price.

Anthropic, for its part, is facing many of the same challenges OpenAI is. It has well regarded, incredibly capable models with widespread adoption. The models are extraordinarily expensive to develop and run, however, and the company is unlikely to recoup these costs, let alone turn a profit, by monetizing consumers alone. Which means that the business and more specifically enterprise sectors are a compelling revenue opportunity. That opportunity, however, is dramatically easier to access via a partner, and whatever else may be said about IBM in 2025, it remains a trusted ambassador within large enterprises globally. Not that this is Anthropic’s first attempt at this route to market – Amazon and Google have both already made large, splashy investments in the startup – but if a relationship with IBM can shortcut Claude’s path to legitimate enterprise adoption even at the margins, that’s an opportunity worth pursuing.

Time will tell about the prospects for this particular partnership specifically and the wider AI market generally, but in the wake of this week’s announcement it seems like a clear opportunity for both parties. What’s left is to see what they make of it.

Disclosure: Amazon, Google, IBM and Microsoft are RedMonk clients. Anthropic, Apple, OpenAI and NVIDIA are not currently clients.