For those that have been in the technology industry for some time, there is a tendency to compare or even equate the current microservices phenomenon with the more archaic Service Oriented Architecture (SOA) approach. This is done implicitly in many cases, but also quite explicitly with statements such as “microservices is nothing more than the new SOA” or “Amazon is the only company to get SOA right.”

This is unsurprising, because it’s rooted in fact. For all of its other faults, SOA was a vision of enterprises that looks remarkably like what progressive organizations are building today with cloud native architectures composed of, among other things, microservices. Stripped to its core, SOA was the idea that architectures should be composed of services rather than monolithic applications.

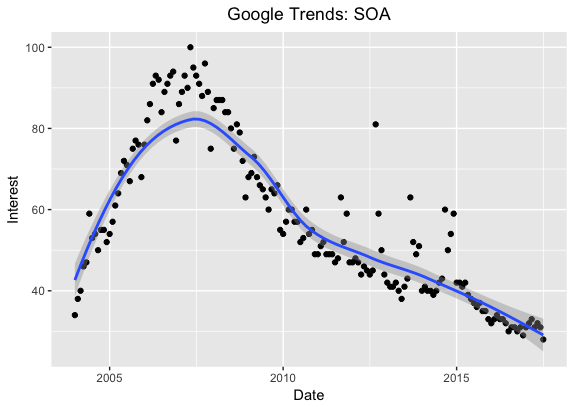

Popular as that vision is today, however, SOA was from the start an uphill battle. It gained hype and currency, which in turn led inevitably to furious messaging and branding pivots, but even in an industry which tends towards the ephemeral SOA’s moment in the sun by the standards of technologies that preceded it comparatively brief.

If SOA and microservices have at least some common ground from a functional perspective, then, why was the former rejected and the latter embraced?

Many would point to size as the critical differentiator. Services as described by SOA were insufficiently granular, it’s been argued, and therefore difficult to build and harder to manage. Setting aside the obvious fact that this glosses over the management overhead associated with taking large services and breaking them up into large numbers of smaller alternatives, it also misses the far more critical distinction: SOA was primarily a vendor led phenomenon, microservices is by contrast largely being driven from the bottom up.

Given the success of platforms such as AWS, it’s difficult to make the argument that service driven platforms are not an effective way of building platforms that scale or that they’re not the dominant approach at present. But notably, service-based platforms are generally developer constructs at present. The SOA-driven world originally envisioned by large vendors, one in which services were built out upon a byzantine framework of complex (and frequently political) “standards” never came to pass for the simple reason that developers wanted no part of it.

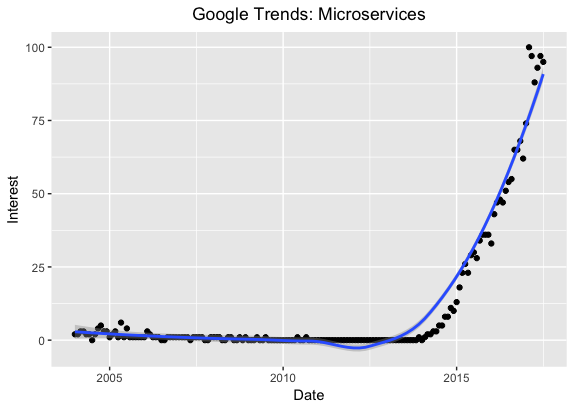

To be sure, microservices has benefitted from the lessons learned by various SOA practitioners, and indeed the effort to popularize and socialize the latter term has simplified the adoption of the former. But the most important takeaway from SOA was arguably that developers would play a decisive – and in many cases, deciding – role on what would get used and what would not. Microservices are easier for them to develop than monolithic alternatives, and come without the vendor standards baggage of SOA, which is why even if it’s still outpaced by SOA on a volume basis its trajectory looks a lot more positive.

Too often in this industry we look for explanations for success or failure based on technology or function, while the real causative factors for success or failure are much simpler: do those would make kings want to use it, or not?