In October of 2005, then CTO of Microsoft Ray Ozzie issued a seven thousand word memo to his direct reports entitled “The Internet Services Disruption.” Addressing the dynamic landscape around internet based services impacting traditionally distributed software, it spoke of both opportunity and threat for Microsoft. “As much as ever, it’s clear that if we fail to [respond to the challenge], our business as we know it is at risk,” Ozzie cautioned.

Seven years later, perceptions of the role of software as a revenue engine are largely unchanged. While delivery models for software have shifted, incorporating new mechanisms such as open source and SaaS, the business models behind them have evolved little. Most software revenue is still derived from a combination of license, support and maintenance fees, as opposed to, for example, application generated data and analytics. At Microsoft, for example, approximately 83% of the revenue is derived from the business units principally (if not exclusively) associated with software: Windows & Windows Live (Windows), Server and Tools (Windows Server, SQL Server, etc) and Microsoft Business (Office). While each of those business units incorporates non-traditional software components – e.g. Azure or Windows Live – the primary revenue engines remain Office and Windows.

Nor is Microsoft alone in its reliance on software models; the majority of large software suppliers (e.g. Oracle) remain primarily oriented around software revenue streams, and have demonstrated minimal interest in diversifying their businesses to hedge against potential challenges to software margins: Exadata is an exception rather than the rule.

What’s unclear is whether the commonly perceived viability of software revenue models is correct, or Ozzie is. Having spent time over the past several years working with software firms and examining the fundamentals of the revenue model, the causes for concern to me are obvious. But what does Microsoft’s actual performance suggest to us?

Microsoft’s revenue figures suggest that they remain able to grow their revenue, if not as quickly as in years past. Revenue growth from 2010 to 2011 was 11%, and from 2011 to 2012 the figure was 5%. Microsoft’s revenue model may be impacted by disruptive services on an ongoing basis, but it has not been crippled as a result.

How reliant is Microsoft on software as a revenue engine, however? What impact can be seen on Microsoft’s revenue picture from Ozzie’s efforts to steer Microsoft towards the leveraging of services as a source of revenue alongside software?

While Microsoft’s Entertainment and Devices and Online Services divisions are able to generate revenue, as demonstrated above (12.4B collectively in 2012), they are thus far unable to impact Microsoft’s bottom line in a positive manner. Over the last three years, Entertainment has been responsible for around 2.4% of Microsoft’s operating income. Online services, meanwhile, has been an anchor, financially speaking: the operating income for the division over the last three years beginning in 2010 was (2.4B), (2.7), (8.1). In 2011, it cost Microsoft 9% more than it did in 2010, and in 2012 Online Services cost Microsoft 67% more than the year prior.

In short, while Microsoft has grown its services business and generated real revenue from them, it has not been able to do so profitably. To date the company’s core software businesses have been able to subsidize this growth without a material negative impact to the company’s share price, though they might be contributing to the stagnancy there, but the financial trendlines are obviously not sustainable over a longer term.

These losses have convinced some investors that Microsoft should decommit from the businesses behind them, by sale or otherwise. This is a reasonable contention if you believe that the margins extractable from software will remain substantial indefinitely. Ozzie was clearly concerned about this prospect moving forward, and I have argued that the realizable margins from software are, in fact, in decline.

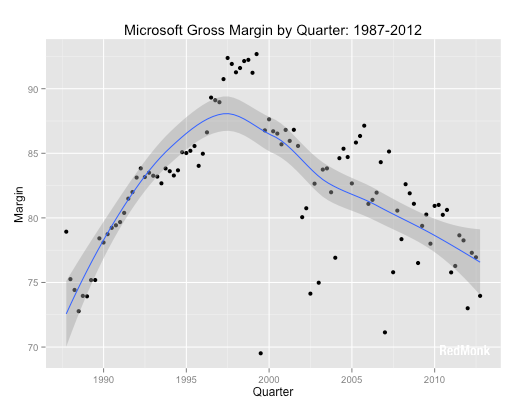

Microsoft itself, as it happens, offers some evidence that this may be true.

Peaking just prior to the year 2000, Microsoft’s margins have been in steady decline since. It’s possible, of course, that this is merely execution on Microsoft’s part as opposed to a broader industry trend. IBM’s consistent ability to grow profit in its software division is one contradictory datapoint. But considering the wider industry trends, from open source to cloud to SaaS to bring your own device, it’s not clear that Microsoft could or should consider a return to a purely software based revenue model.

Its losses otherwise notwithstanding, Microsoft is probably best served identifying the specific failures of its non-core software businesses rather than jettisoning the models entirely. If our assertions about the longer term direction of software licensing are correct, in fact, they may have no other choice.

For the foreseeable future, it will remain possible to monetize, at a healthy margin, software. But it is getting more difficult to do this every year, as the competitive threats multiply from unanticipated directions. While software is critically important to Microsoft, then, the company’s future could depend on it becoming less so.