“Building web apps is not getting easier. The fragmentation of operating systems and browsers is getting worse, not better.”

– Fred Wilson, “Fragmentation”

With a few caveats, the above statement is obviously true.

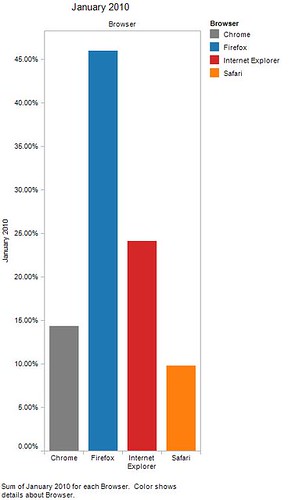

We don’t see quite the same level of fragmentation that Wilson does; his property has five operating system and browser combinations with better than a 10% share, while we have only three. No platform has better than a 17% share there; we have two north of that figure. But if we split the metrics, our data shows the same trajectory. Here’s our browser system share for January of this year, for example.

No real surprises, at least for us. Firefox is dominant, IE a distant second with more Chrome traffic than Safari. But now look at the numbers from the past thirty days.

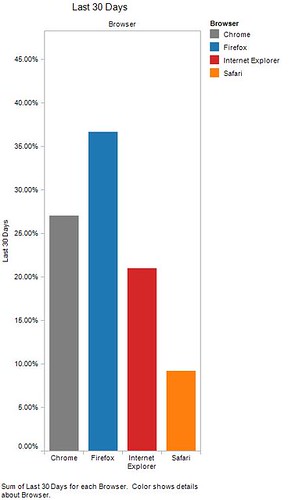

Things are much tighter. Firefox is still the leading browser, but its advantage has been eroded substantially by Chrome, which in the same span passed IE for second place. There are a variety of browser specific conclusions that might be drawn from this data, but what we’re interested in is this: we’re heading towards multiple platform parity. Witness the standard deviations.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with standard deviation, the concept is simple: it measures how far values are from the average of all of them. Practically speaking, that means “how widely distributed a sample is.” If the standard deviation is large, the values are all over the map. If the standard deviation is small, the differences between them are smaller.

The standard deviation in January? 16.11. The past thirty days? 11.49. What this means is that the differences between the marketshare of each browser is decreasing. The implications from a developer perspective are obvious: it’s easy to support one or two dominant platforms reliably. It’s much harder, however, to support four or more platforms that have roughly comparable adoption.

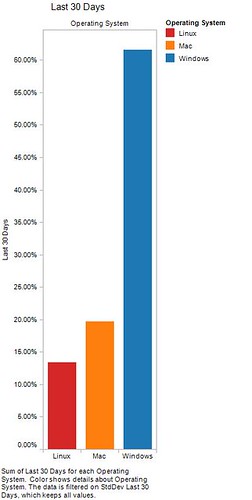

The differences from an operating system perspective are more slight. Here’s January of last year.

Some growth for Linux at the expense of – apparently – both Mac and Windows, but overall the delta is minimal. As the standard deviations indicate: 27.31 for January against a 26.21 the last month.

Still, slow as that process might be, the trajectory for operating systems is towards a flatter, more diverse landscape. And we’re not taking into account here the rise of new mobile platforms because the cut off for the above is platforms with at least 5% share. The iPad, as an example, has gone from 0% traffic in January to ~2% in less than 12 months. Android, meanwhile, is about 1%, a figure likely to rise once tablets running that platform begin hitting the market Q1/Q2 of 2011.

The data, then, concurs with Wilson: fragmentation – or parity, if you prefer that term – is accelerating. And actually, it’s a far bigger problem than those numbers indicate. True, web application development is (still) a problem. Also, as Wilson points out, developers and enterprises alike are increasingly vexed by the choice between native mobile development – Android, iOS, RIM, Windows 7, etc – versus web applications.

But traditional server side development is at least as challenged.

Start with languages. The days where businesses picked one of Java or .NET – or at least the perception that that was the case – are long gone [coverage]. Likewise, the era of LAMP being the default stack for web startups has come and gone. Enterprises are increasingly augmenting their officially sanctioned Java and .NET stacks with PHP, Python and Ruby. Today’s startups, meanwhile, have moved on from those to Clojure (e.g. BankSimple), Scala (e.g. Twitter) while returning to Javascript with a vengeance.

In between these languages/runtimes and the application sit a host of frameworks. From the established (e.g. Django, Rails, or the Zend Framework) to the up and coming (e.g. Lift, Node.js), frameworks are an additional abstraction developers are turning to to eke out incremental time to market gains, to maximize performance, to eliminate repetitive development, or all of the above. By my count, thirteen of the top fifteen Interesting repositories on Github are framework projects of one kind or another; the two exceptions are mirrors of the Git and Linux trees.

Even the data layer has not escaped this Cambrian explosion in diversity, to borrow Brian Aker’s metaphor. Time was when the question came to data persistence, the answer was a relational database. Today, we have, effectively, at least one option per workload type, from relational to document to columnar to key value store to graph to distributed file system.

Nor is hardware a straightforward selection. While the market has largely trended towards x86 from a server perspective, issues concerning power efficiency are beginning to raise questions about the viability of alternative server side chipsets such as ARM. The cloud, meanwhile, forces developers to compare the capex advantages offered by pay-as-you-go hardware with the potential opex benefits to owning your own gear.

We could keep going, but the conclusion is clear: it’s turtles all the way down. At every layer, developers have more choice. Which, as Barry Schwartz reminds us, is a mixed blessing at best. It’s easier to get building on LAMP, for example, than to evalute the relative merits of Node.js vs Twisted.

This explosion of choice will, inevitably, trigger a reaction, which is likely, in turn, to be reactionary. Consolidation will not eliminate choice, but it will reduce it as the lack of available oxygen eliminates or compels the merger of adjacent projects. In the meantime, however, life for the developer should be at once rich and complicated. The toolkit has never been fuller, which means that the benefits of improved tooling will in some circumstances be offset by the challenge of evaluating and selecting it. At least initially: over time and at scale, even marginal performance wins can add up.

Fragmentation is real, fragmentation is here, and fragmentation isn’t going anywhere. Adjust your strategies accordingly.