“Recall that DNA transmission among single-celled bacteria and viruses is far more promiscuous than the controlled vertical descent of all multicellular life. A virus can swap genes with other viruses willingly. Imagine a brunette waking up one morning with a shock of red hair, after working side by side with a redheaded colleague for a year. One day the genes for red hair just happened to jump across the cubicle and express themselves in a new body. It sounds preposterous because we’re so used to the way DNA works among the eukaryotes, but it would be an ordinary event in the microcosmos of bacterial and viral life.”

– The Ghost Map, Steven Johnson

Bacteria – viruses too – evolve more quickly than do humans. If you’re reading this, that should not be a surprise. The precise mechanisms may be less than clear, but the implications should be obvious. Part of their advantage, from an evolutionary standpoint, is scale. There are a lot more of them than us, and each act of bacterial reproduction represents an opportunity for change, for improvement. Just as important, however, is the direct interchange of genetic material. As Johnson says, it sounds preposterous – absurd, even – because we are used to linear inheritance, not peer to peer.

We see a similar philosophical divide in between those who abhor the forking of code, and those who advocate it.

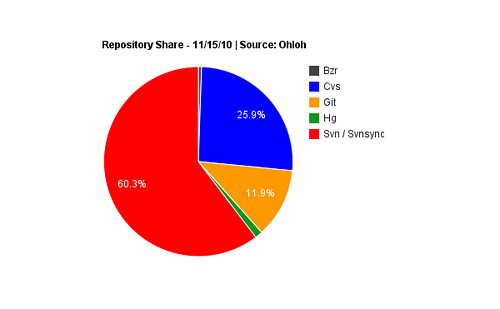

Examples of the former abound. The fear of forking remains rampant in spite of the rise of Git, Mercurial and the other decentralized standard bearers. Perhaps because instantiations of Git and its decentralized brothers, for all of their popularity amongst the developer elite, remain heavily outnumbered by the legacy version control alternatives. Looking at Ohloh, for example, which indexed better than 238 thousand projects, we see the following traction for individual DVCS systems (note that I’ve conflated the Svn and Svnsync numbers in the original graph).

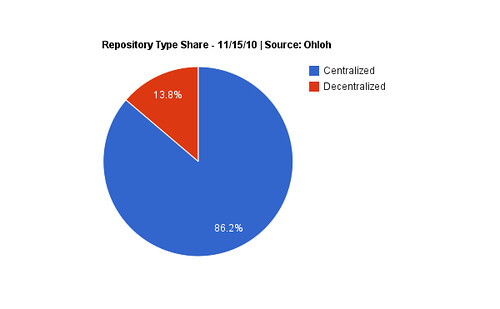

Interesting, but the specificity of this graph is counterintuitively working against us, telling us less than it could about the larger adoption trend. Let’s look at the same data, but filter by repository type rather than repository name.

This is more clear: centralized repositories still dominate the market. Provided that we assume that this dataset is representative of the wider version control landscape. And while the sample size is more than adequate, there are actually caveats to this data: Github, for example, is not indexed by Ohloh to the best of my knowledge. Of course, neither are the countless inside-the-firewall CVS deployments at enterprises all over the world. In short, while the data is by necessity imperfect, it can be used for making educated guesses at adoption. That centralized tooling significantly outnumbers decentralized alternatives seems to be a safe conclusion; the uncertainty lies rather in how big the lead is.

Also, how long that lead will last.

Because the more logical explanation for the fear of forking doesn’t lie in the relative scarcity of distributed version control: it is nothing more or less complicated than the fact that it is a fundamentally different way to develop software. Doubtless its champions would cringe at the comparison, but development with DVCS tools has more in common with how bacteria reproduce than with humans: forking promotes distributed, peer to peer evolution, in which many copies evolve more rapidly than a single one could linearly.

As has been pointed out in this space before, even smart people struggle initially with the concept of distributed development. “I don’t believe in it,” is what an otherwise pragmatic CTO type of a major exchange told me a few weeks ago about distributed version control generally, Git specifically. “My developers work next to each other – they keep bugging me about it – but if we had branches everywhere we’d be stepping all over each other.” This remains, for better or for worse, the majority opinion in the enterprise. But the enterprise isn’t the only one with trust issues when it comes to decentralized development. Here, for example, is Brian Aker – a believer in active forking – on the subject:

On a related note there was a recent phone call that O’Reilly put together with a number of open source leads. It was amazing to hear how many folks on the call where terrified of how Github has lowered the bar for forking. Their fear being a loss of patches. It was crazy to listen too.

Joel Spolsky captured perfectly the disconnect that even smart developers can have when initially trying to wrap their minds around a Mercurial:

My team had switched to Mercurial, and the switch really confused me, so I hired someone to check in code for me (just kidding). I did struggle along for a while by memorizing a few key commands, imagining that they were working just like Subversion, but when something didn’t go the way it would have with Subversion, I got confused, and would pretty much just have to run down the hall to get Benjamin or Jacob to help.

When developers arrive at that point in the DVCS learning process, there seem to be essentially two paths forward. The easier is to give up. Lick your wounds and retreat to Subversion if you’re lucky, CVS if you’re not. The harder thing to do is to try again. To trust that the growing if still nascent traction for DVCS tools will more than offset the initial discomfort with the model. Typically, this leads to an epiphany, which arrives in two parts. First, you realize that DVCS enabled forking isn’t bad. Core to this phase is the realization that an increasing number of successful open source projects are by choice built using distributed version control systems. Riak has been DVCS from day one, only recently migrating from Bitbucket (Mercurial) to Github (Git). Speaking of GitHub [coverage], they’ve got a few projects you’ve probably heard of: jQuery, Memcached, MongoDB, Redis, Rails, and the Ruby language itself. Git, for its part, was originally written to manage the development of the Linux kernel. Developers are smart: once they’re better acquainted with this history, it becomes harder to sustain the mindset that distributed version control is somehow wrong. If it was, the continued traction would be improbable.

From there, deeper experience triggers the realization that DVCS tools are good. Great, in fact. That distributed development, and the friction-less forking it enables, is actually a real positive for development speed. Spolsky went through just such a conversion, and would up convincing himself that decentralized development “is too important to miss out on. This is possibly the biggest advance in software development technology in the ten years I’ve been writing articles here.”

Technology is, more often than not, a pendulum: swinging back and forth between extremes [coverage]. This is not the case with version control software. It is possible – likely, from a historical standpoint – that distributed tools such as Git will be themselves replaced by as yet unforeseen source code management tooling. But we will not be going back in the other direction. The advantages to distributed development are too profound to be abandoned. Organisms that evolve more quickly adapt more quickly, and Darwin tells us that organisms that adapt more quickly survive. Distributed source code tools are proving this true in code every day.

In other words, it might be time to get over your fear of forking.