Daniel Case, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

It can be difficult to remember in the wake of PostgreSQL’s ongoing renaissance, but MySQL was for decades the default open source relational database, which in those days meant it was the default open source database. While the former’s evolution from Ingres was unfolding slowly over the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, MySQL was developed in 1994, released in 1995 and capitalized on the growing popularity of open source to become nearly ubiquitous. It was the default database in the most popular open source tech stack of the time, LAMP, and most developer texts assumed MySQL as the database.

While both MySQL and PostgreSQL were both open source databases, however, their development models were quite distinct. MySQL was built on a dual license model, which allows customers to buy their way out of the licensing terms of the GPL they cannot or choose not to comply with. To be able to issue a dual license, however, MySQL has to own copyright to all of the code outright. In practice, this meant that the development burden was almost entirely on MySQL, because few commercial organizations are willing to write code just so another commercial entity can exclusively monetize it. This was and is the single entity open source model.

PostgreSQL, by contrast, was originally released not under a more restrictive copyleft license like the GPL, but the vanity PostgreSQL license with terms similar to the permissive MIT. Because the license imposed essentially no restrictions on usage of the project, any and all parties were free to use, modify and distribute the software as they saw fit – even if that meant closing the project off and making it proprietary. This licensing choice involved a trade off. On the one hand, no one vendor could exclusively monetize the software, but on the other, it allowed for the growth of a wider ecosystem with more participants in the project. Over time, PostgreSQL became a canonical example along with others like Linux of a multi-entity open source project, where multiple parties – even competitors – come together to collaborate on a project collectively.

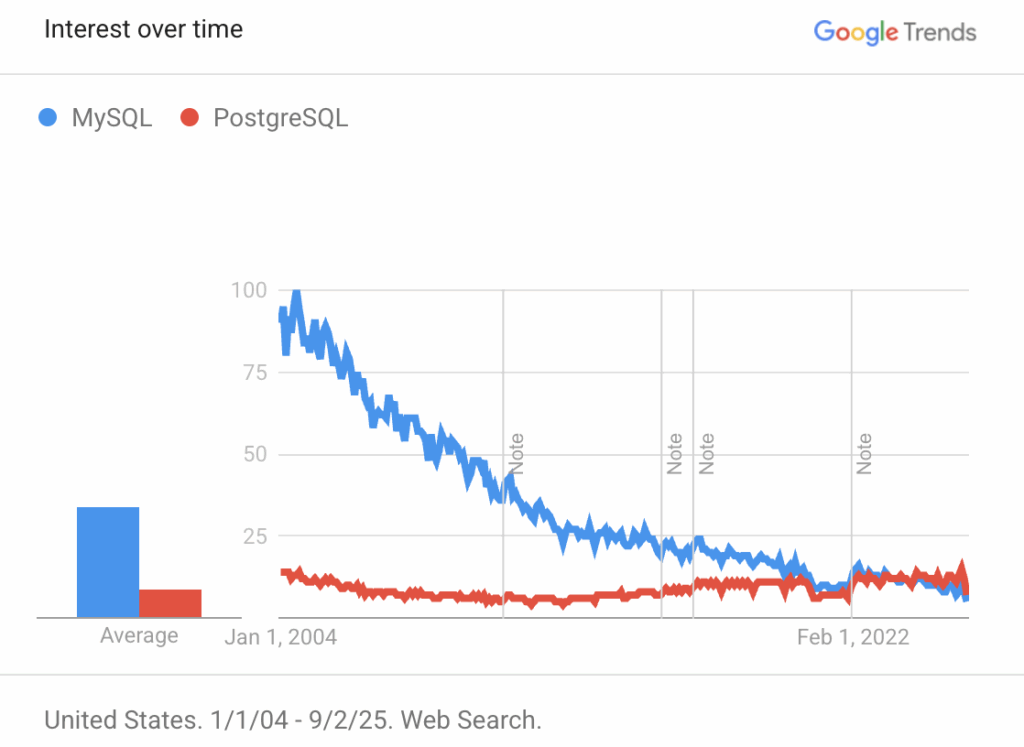

For the better part of a decade after MySQL’s release, and for a wide variety of reasons, it dominated PostgreSQL from a visibility standpoint. Since that time, however, its dominance has steadily eroded as Google Trends documents here.

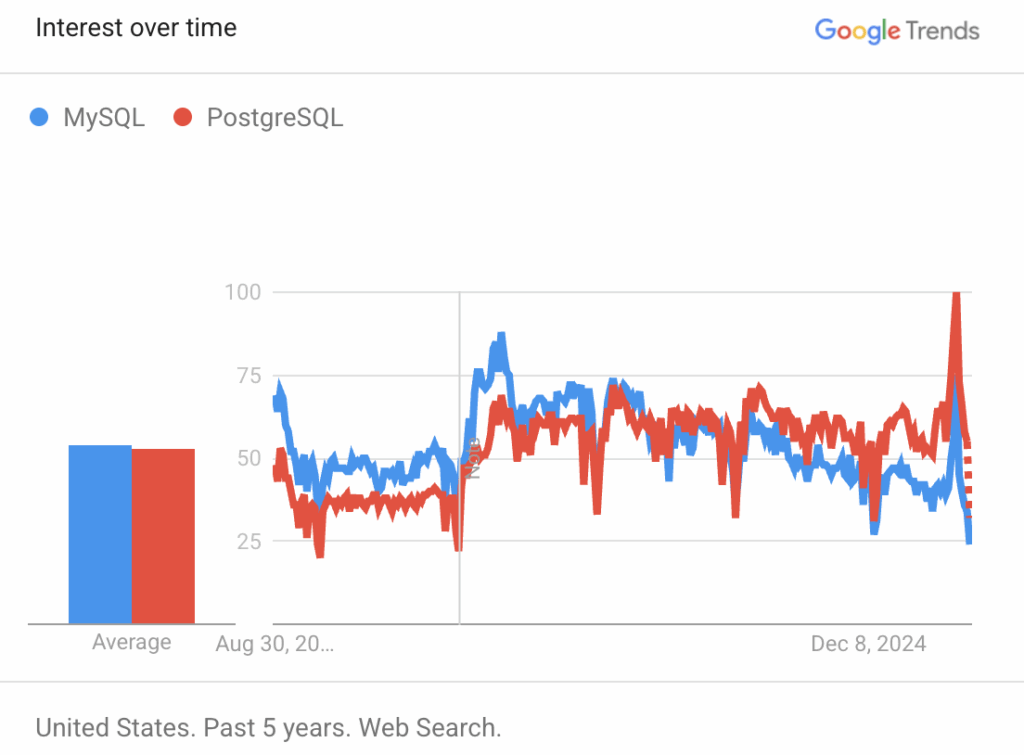

Eroded to the point, in fact, that MySQL has been surpassed by PostgreSQL at least in public visibility over the last five years.

MySQL is still an enormously popular database, to be clear. But it is no longer the dominant project, nor the default. It has ceded that title to PostgreSQL. Where, for example, did Databricks and Snowflake turn when their growth from data lake to more broadly capable data platforms required relational database capabilities? To PostgreSQL vendors – Neon and Crunchy Data respectively. When developers are building applications today, more often than not the assumption is that the database will be PostgreSQL, not MySQL.

There are many reasons for this change in fortunes, and no single project characteristic is responsible for it. But PostgreSQL advocates and vendors typically point to the advantages of its broader community, which again is enabled by its liberal license. Multi-entity open source means more commercial options, which large enterprises favor because competition limits vendors’ leverage with respect to pricing and it limits their risk to vendor behavior and changes. It can also mean broader project support and faster innovation, as evidenced by the speed at which PostgreSQL has been able to adapt to emerging market demands by adding the ability to handle new workloads from JSON to vector.

At present, then, the market is favoring a multi-entity solution for its relational database needs. Redis, meanwhile, dominated the in-memory key-value category for years, but a licensing change created a rift in that community and opened a path for a multi-entity Redis alternative in Valkey. The jury is still out on which path the industry will choose in that case.

All of which brings us to DocumentDB.

Not, oddly enough, the AWS product of that name. Microsoft, apparently, has its own project called DocumentDB which it has donated to the Linux Foundation. This raises an immediate and obvious question about the DocumentDB trademark, but without any answers available that will have to be set aside for the moment other than to note that the LF now owns it.

Microsoft’s DocumentDB is a project built, in essence, to layer MongoDB API compatibility on to a PostgreSQL database. Unlike MongoDB, which is licensed under the non-open source Server Side Public License (SSPL), DocumentDB has been released under an MIT license. That licensing choice, along with its donation to a neutral foundation, is presumably why it was able to attract support from AWS, Cockroach, Crunchy, Google, Supabase, Yugabyte and others joining Microsoft in the launch.

This is not, of course, the first attempt at providing a MongoDB compatible alternative database. Microsoft’s Cosmos DB has been offering this for years, as has AWS with DocumentDB and more recently Google announced MongoDB compatibility for its Firestore product. Percona, meanwhile, offers vanilla MongoDB support. Lastly FerretDB, for its part, has also loudly and prominently positioned itself as a drop-in MongoDB alternative, to the extent that the latter party took exception and sued the former.

Prior to April 2021, MongoDB’s claims likely would have included copyright violations, but in the wake of Google v Oracle, those would seem unlikely charges to be sustained. Instead, MongoDB has alleged patent infringement, misuse of its trademark and unfair competition. As that litigation is still pending, there’s not much to take away from it and it could well be a simple tactic rather than a genuine attempt to prove the claims.

What we know, however, is that MongoDB – unlike some other examples here like Redis – is a single entity project. MongoDB is responsible for the entirety of their codebase, which is why they were able to unilaterally relicense the project from the AGPL to the SSPL in 2018. The SSPL, in fact, is an attempt to preserve MongoDB’s exclusivity by increasing the friction to offering the database as a service.

On the one hand, all of this attention and competition can in some sense be regarded as flattering to MongoDB. Out of all of the possible database projects and document databases, the industry has de facto agreed on MongoDB’s API as the industry standard. It is also possible that being that de facto standard will increase – potentially dramatically – the size of the addressable market, thereby offering MongoDB a larger opportunity to target.

On the other hand, the company clearly believes, as many of its database peer companies do judging by the licensing trends, that exclusivity is key to its present and future success. What’s difficult to see, however, is how that’s achievable in a world in which the Supreme Court has strongly suggested that copyright does not apply to APIs and all three large hyperscalers, the largest open source foundation and a selection of startups all feel comfortable from a legal standpoint publicly invoking MongoDB’s name.

One potential response might be found in the consumer packaged goods sector. It has been common practice for years to have a store brand, and a premium brand. In many cases they are the same, or at least a highly similar, product, and yet the premium brands survive because consumers are willing to pay a premium for an item perceived to be higher value.

The biggest and best opportunity for this model in the technology sector, coincidentally, also came from Microsoft. Many years ago, it was argued in this space that Microsoft – whose .NET stack and C# language were highly regarded technically but virtually non-existent outside of its own Windows ecosystem – could and should have given both of those products a chance to better compete via the Mono project. Originally the brainchild of Ximian, Miguel de Icaza and Nat Friedman’s open source startup, Mono was an alternative, open source friendly .NET runtime. Simply by offering the project a patent amnesty, and thereby removing the Damoclean sword of potential IP litigation, Microsoft could have overnight given itself a credible .NET story for the flood of new Linux servers arriving in market every day. Importantly, it could also have sold effectively against the alternative stack by positioning itself as the premium brand to the store brand. Unfortunately, however, this model was never tested as open source itself was anathema to Microsoft at the time, and a third rail issue that would never go anywhere strategically.

However MongoDB the company navigates the DocumentDB project announcement, it will be worth tracking more broadly the performance of single entity open source projects versus the growing popularity of multi-entity alternatives. Project and product selection is rarely if ever likely to come down to that single characteristic and product decisions are inherently more complicated, but the industry – buyers and sellers of technology alike – is increasingly investing into open source communities that are licensed in such a way that they cannot be controlled by one single entity. What the returns on those investments will be in future will have an enormous impact on the direction of the industry and the health of open source itself.

Disclosure: AWS, Crunchy Data, Google, Microsoft, MongoDB, Oracle (MySQL) and Percona are RedMonk customers. Cockroach, Databricks/Neon, Redis, Supabase and Yugabyte are not currently customers.