It wasn’t appreciated much at the time, but for a couple of decades there the technology landscape was pretty easy to understand. Not the implementation details, necessarily. At a basic level, the Icelandic translation for computers – “numbers witch” – is appropriate, because the devices are arcane, and dimly-understood elemental instruments capable of wildly unpredictable and unexpected outputs.

But for a while, it was enough for company leadership to understand that they owned a bunch of hardware that ran in a facility they also owned that was the platform upon which a software stack (also owned), that was constantly behind what the business wanted, was hosted.

There were exceptions at the margins, of course, from time sharing in the early days to colocation later in the game, but most large businesses wanted to own their software, the hardware it ran on and the real estate that served as its home.

A different world began to emerge, and emerge quickly, following the introduction to two of the most important cloud primitives – compute and storage – by Amazon Web Services in 2006. Within short order, architectural discussions that once could safely assume a single, company owned datacenter dominated by scale-up approaches found the ground shifting under their feet. Seemingly overnight, a second, and increasingly more popular model of machines operated by a third party hosted in datacenters owned by them rented by the hour – what we today would refer to as Infastructure-as-a-Service – became first a player and then the player in these converations. While the acceptance of cloud into mainstream enterprise conversation hardly happened overnight, relative to other architectural revolutions such as client server, the process was rapid.

A few short years then after the cloud market was created, discussions were characterized by clarifications as to what was “on” and what was “off” – premises, that is. This distinction has served and served well up until fairly recently.

What’s becoming apparent, however, is that whatever bright line once existed between on and off prem is becoming less so by the day. From the original Azure Stack (software running on customer premises) to Anthos (cloud middleware run on prem or in other clouds) to Outpost (cloud hardware/software running on prem) to Local Zones (localized clusters of cloud hardware software) to Wavelength (hardware/software embedded with carriers), it’s becoming more and more difficult to tell the difference between what is cloud and what is on prem.

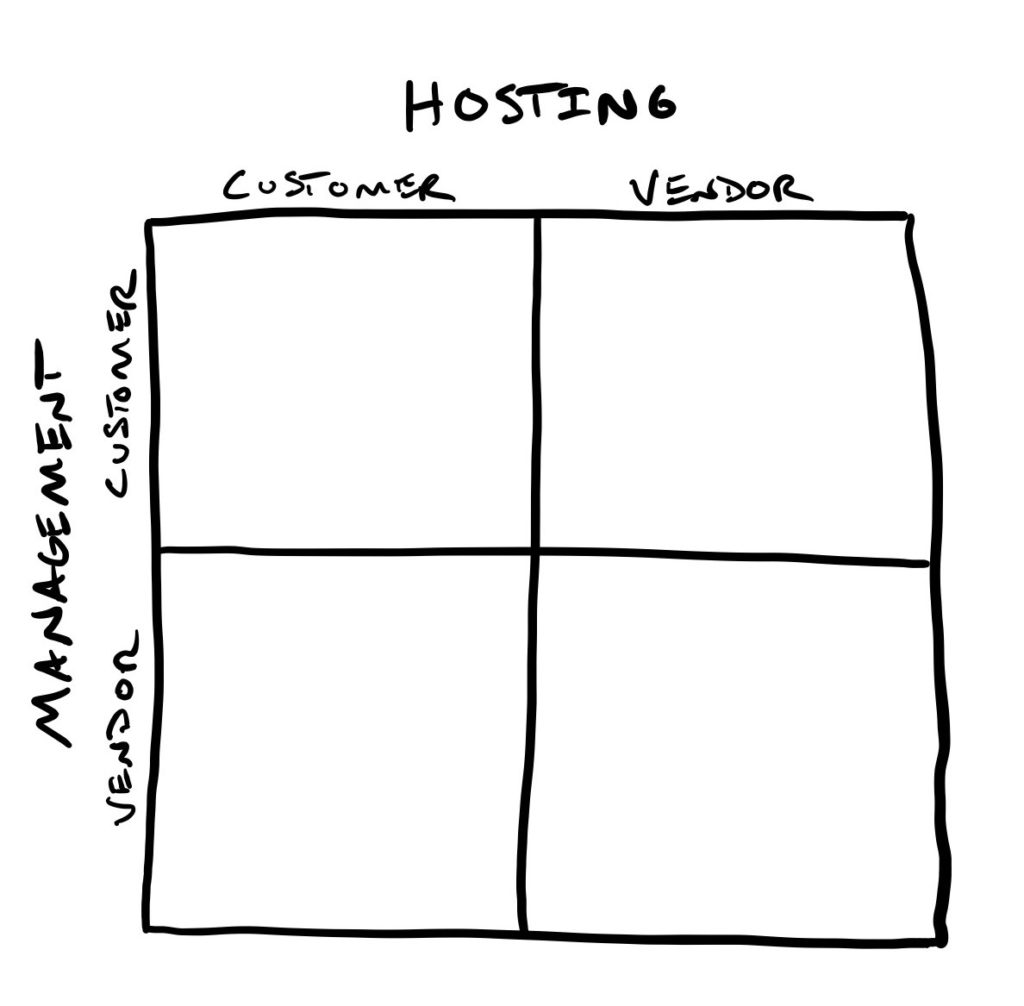

Which, in turn, requires the market to understand and appreciate nuance; in addition to the traditional scenarios of hosted and managed by customer or vendor, we’re seeing an increasing number of combinations. In an attempt to help clarify exactly where the responsibilities may lie, we’ve used the above matrix in discussion with both users and customers. A two by two matrix self-evidently won’t capture all of the possible parameters or permutations, but it at least tries to broadly clarify where something is being run and who’s operationally responsible.

If you’re having conversations like this, or more particularly are advocating for internally or building tools that don’t fit within the bounds of traditional classifications, it’s possible that you might find this framing useful.

Either way, if recent launches and some of the product roadmaps we’re privy to are any indication, the need for the market appreciation and understanding of the hybrid hosting and operational models is only going to become more acute.