If the days of software licensing as a primary revenue mechanism were over [coverage, coverage], how would we know? How might we test the hypothesis that the value of software in a commercial sense is declining over time? Logically, lower commercial valuations for software would necessarily manifest themselves within organizations that derive a majority of their income from software sales; so evidence should be apparent in their reporting. While this approach limits us to organizations that break out their revenues in sufficient detail, fortunately one entity primarily oriented around software – Oracle – provides us with the necessary data on their annual reports.

In the consolidated statement of operations within their annual 10-K filings, Oracle not only separates software revenues from hardware and services, it breaks out revenue atttributable to new software licenses versus existing license updates and support agreements. This allows us to understand more accurately the importance of software to Oracle.

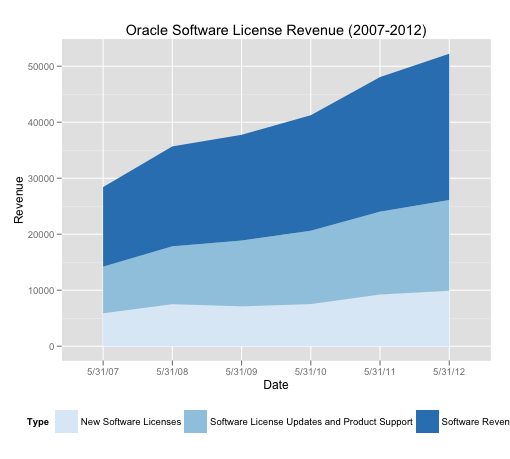

To begin with, we can examine the growth of its software business over time. For this sample, we’ve looked at six years worth of financial data, from 2007-2012. If we plot the growth of new software licenses, existing license and support agreements and software revenue overall, a few things become apparent.

First, we can see that Oracle has been able to substantially grow its overall software revenue in spite of the global recession. Software revenues almost doubled over that span, in fact – economic meltdown or no. The majority of that growth, however, does not derive from new software licenses. The percentage of overall software revenue from sales of new licenses, in fact, is down three percent over that period. Revenue growth from new sales, in fact, is growing roughly half as fast as growth from what Oracle terms “Software license updates and product support.” Which means that Oracle is, comparatively, finding sales of new licenses for new products more challenging than support and service for existing customers.

Beyond the individual components of software revenues, there is software itself as a component of Oracle’s overall revenue picture. What role does software play today, and how has that changed over the past six years?

Peaking in 2009 – the year it announced its intention to acquire Sun Microsystems – the percentage of revenue Oracle extracts from its software businesses is sharply lower since. For the three year period beginning in 2007, Oracle’s software business accounted for 80% of all revenue earned; for the three year period following, software was down to 72% of total revenue. Averaging the last two years, and that number drops to 69%. Hardware, meanwhile, went from zero percent of revenue in 2009 to 17% this year.

Clearly the acquisition of Sun played a major role in the shift, as Oracle’s decision not to spin off the hardware business signalled its intent to become a more diversified systems player, one less singularly focused on software. But this is also evidence that an organization primarily oriented around software is hedging against potential declines in achievable software revenues.

An examination of Oracle’s financials, then, challenges our hypothesis by demonstrating consistent revenue growth from its software business, especially adjusting for the context of a global economic crisis. It does suggest, however, both that growth from new software licenses is slowing and that software’s dominance as a revenue engine has weakened over the past six years.

Oracle is today and will be for the forseeable future a software company first, hardware and services second. But the evidence suggests that it should be and in fact is preparing for a future in which its software revenues are challenged.

Disclosure: Oracle is not a RedMonk customer.