Two days ago, two analysts from UBS – Brian Pitz and Brian Fitzgerald – projected Amazon Web Services revenues at $500 million. Many were disappointed, expecting more from the widely acknowledged market leader: a half a billion dollars is approximately what Microsoft spent per datacenter pre-2010.

Those who would focus on the actual revenue figure, however, are likely to miss the more important margin numbers.

It has been long assumed that cloud computing – at least as currently practiced by the lower value add Infrastructure-as-a-Service practitioners – is a low margin business by enterprise infrastructure standards. Larger systems players such as HP and IBM have shown little appetite for the public cloud market in part because of this, depending on who you talk to. One senior executive I spoke with from a large systems vendor two years ago was blunt in his assessment of the prospects for a public cloud offering: “I don’t want to be in the hosting business.” The implication being that hosting offered insufficient margins.

Certainly nothing in Amazon’s pricing, either at launch through to today, has seemed to contradict this conventional wisdom. True, the actual cost of full-time EC2 instances exceeded competitive offerings from traditional hosts, but the dynamic consumption of AWS servers would presumably mitigate the moderate margin Amazon could realize. A half month of a $72 dollar server is worth less than a full month of a $40 server and so on.

Except that it apparently isn’t.

At the OSCON Cloud Summit, I delivered a presentation on cloud lockin. The concept as it relates to margins was simple: margins at the foundational layers were slimmer, which was spurring the development of various platform services which besides creating the potential for lock-in would theoretically provide higher margins. It’s standard technology value-add thinking: if I can charge $10 for a basic, bare bones server, I should be able charge $20 for a platform in which you don’t worry about servers, capacity planning and such any longer. That the market has largely rejected platform services in favor of more elemental infrastructure building blocks doesn’t change the basic economic assumptions being made.

My presentation was, I believe, generally well received. The reactions, both on Twitter and in person following my talk, were positive and question oriented. With one notable exception.

James Watters argued vigorously that I was underestimating, substantially, Amazon’s margins.

WOW @sogrady couldn’t have been more wrong when comparing the margins of HP to EC2; EC2 much higher than HP average 25%.

Partially the disconnect is that I hadn’t meant to imply a comparison of cloud margins to that of HP generally. The intent was rather to contrast typical cloud margins to enterprise technology businesses, where ideal margins generally begin at 40%. But as it turns out, James was right and I was wrong, irrespective of that framing error.

According to UBS, Amazon Web Services gross margins for the years 2006 through 2014 are 47%, 48%, 48%, 49%, 49%, 50%, 50.5%, 51%, 53%. Granted, this is an analyst projection. And the inherent risk of projecting four years out in a volatile market is acknowledged.

But even should we trim the figures liberally, the fact is that the margins that Amazon is realizing on basic infrastructure services are substantial. For context, look at the income statements for a Cisco, an IBM or an HP.

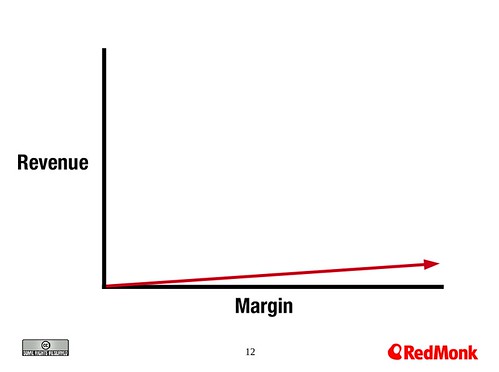

If this is true, most of what what we’ve believed about Amazon’s business – that it was in fact a high volume over low margin business – is wrong. And if that’s wrong, it changes the way we must evaluate the cloud industry and the attendant economic opportunities. Revenue is a function of volume and margin. The volume, with respect to the cloud, is not a concern for me. The margin always has been. If that concern can be erased through combinations of automation, efficiencies and scale, then the economics of the cloud look even brigher than they did before. The current market size may portend less upside that we’ve historically seen from technology sectors because it’s more significantly driven by volume than in years past, but I have few concerns about the market potential long term.

Which is good news for the industry as a whole, I think. Sometimes it’s good to be wrong.