When Apple launched the iPhone in 2007, they correctly anticipated that having what was a reasonable proxy of the real internet on their phone would cause users to consume more data. It can be assumed, therefore, that it was Apple rather than AT&T who pushed for and got unlimited data plans for their customers, to avoid the overage horror stories that would have been the inevitable result of a launch with traditional plans. Thus it was that every iPhone could browse the web with the comfort of knowing that they had, at least in theory, unlimited data.

By now, everyone knows how that turned out.

AT&T’s network was overwhelmed by the “Hummer” of cellphones, its broader network availability declined, and its brand became synonymous with poor performance. Paradoxically, the exclusivity that AT&T bargained for and which won it millions of new subscribers became a liability for the carrier.

From an industry perspective, there are essentially two responses to this problem. One, overprovision network capacity. Two, end unlimited data plans and cap usage. The wireless carriers, at least domestically and in the short term, are trending towards the latter. Whether the primary driver is network reliability or ARPU is debatable, but the end result is inarguable: bandwidth costs are going up, dramatically.

While AT&T would have placed me among the 98% of regular users, the usage patterns of the original iPhone bandwidth hogs – the ones who brought AT&T’s network to its knees – probably looked something like mine. Massive consumption of webpages and regular usage of streaming services, intermingled with higher bandwidth video tasks. Mostly YouTube, back in the days before the availability of NetFlix on what is now called iOS. Remember, the original iPhone didn’t even launch with 3G: it was EDGE only. How much video do you think people were really consuming over a connection that’s a single digit multiple of dialup speeds?

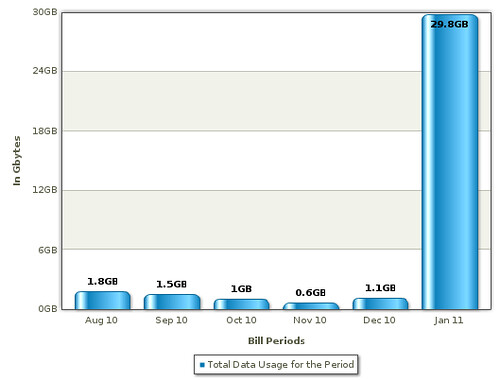

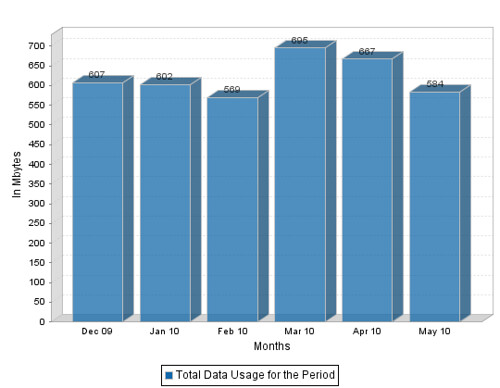

How much data does that usage represent? For a six month period for me last winter, it looked like an average of 624 megabytes a month.

This year, my average consumption from August through December on my grandfathered “unlimited” data plan was up to 1.2 GB. Still comfortably under the 2 GB cap of AT&T’s new tiered medium sized data plan, in other words.

Then came January, when I discovered NetFlix Watch Instantly.

The jump in this graph is attributable to NetFlix’s online movies, but it just as easily could be MLB.tv consumption (assuming they would remove their antiquated blackout restrictions). Or Hulu Plus. Or Rdio. Or Amazon Unlimited Instant Videos. Or Google Music, if or when that gets here.

Expanding device storage capacities notwithstanding, streaming is going to define the mobile experience for many, either because the content is being transmitted live (e.g. MLB.tv) or because you’re only renting it (NetFlix, Rdio, et al). Or at least it would, if mobile pricing permitted it. Which it most certainly does not.

AT&T, of course, no longer has an unlimited data plan for smartphones; their largest is 4 GB ($45/mo) with a $10/GB overage. Of the major domestic carriers, three have unlimited dataplans for smartphones still available: Sprint, T-Mobile and Verizon. What’s not clear is just how unlimited their unlimited data plans really are. Here’s the fine print from T-Mobile’s T’s&C’s, for example:

To provide the best network experience for all of our customers we may temporarily reduce data throughput for a small fraction of customers who use a disproportionate amount of bandwidth. Your data session, plan, or service may be suspended, terminated, or restricted for significant roaming or if you use your service in a way that interferes with our network or ability to provide quality service to other users.

The available plans for laptop or tablet users are even less user friendly. Precisely none of the carriers dare provide unlimited connections for devices larger than a smartphone.

Verizon’s largest non-smartphone mobile data plan is 10 GB ($80/mo), with a $10/GB overage fee. AT&T’s is 5 GB ($60/mo), with a brutal $0.05/MB overage fee; Sprint’s is the same at $59.99/mo. T-Mobile’s basic plan isn’t much better, with their maximum size plan capped at 5 GB ($39.99), but at least they have no overages: after 5 GB, “data speeds may be reduced.”

To put this in context, here is what my January bandwidth consumption would have cost on the various carrier’s mobile broadband plans, assuming an overage of 24.8 GB against 5 GB service plans. Yes, the X axis is in dollars.

The irony of the trendline here is clear from a customer perspective: the demise of unlimited data plans roughly coincided with the introduction of services (NetFlix, Hulu+, etc) that made them attractive. Network operators must take measures to secure their networks, of course, but it is worth questioning whether the carriers are over rotating in an effort to not become the next AT&T. There is little debate that the iPhone swamped an underprovisioned network; the question instead is how much of this was driven by the artificial market factor of Apple and AT&T’s exclusive deal rather than organic growth in data consumption.

Whatever the answer to that question, it is clear that the appetite for mobile bandwidth will grow exponentially over the next twelve to eighteen months. With high volumes of smartphones shipping, more and larger form factors entering the market, and the accelerating build out of streaming services, bandwith consumption is set to spike. Equally apparent is that the carriers are ill provisioned to address this demand, both from a network capacity perspective as well as with their pricing structures.

The takeaways for developers?

- For better or for worse, data consumption is going to be a user concern moving forward. Applications that assist users in their management of same will find a market.

- Developers should aggressively explore native DRM frameworks, because if content streaming is cost prohibitive while on mobile data, local secured storage may be advantaged.

- Developers of streaming applications should a.) heavily optimize for minimal bandwidth, b.) be cognizant of the differentiated data pricing between device types (e.g. smartphones vs tablets), and c.) be network status (wifi or 3G) aware. Customers that are presented with large overage fees due to the consumption of streaming services are unlikely to be happy customers.

- Even for web applications, caching, minifying and offline persistence – historically important to maximize performance on mobile clients – will remain so to minimize bandwidth consumption.

- For certain use cases, native clients may be advantaged against network enabled alternatives.

For everyone else? Repent, for the mobile data apocalypse is upon us.